What would you do if you were making breakfast and looked up and saw this little face peering at you over the pass-through? And yes, note the expectant little paw placed just so off to the side. Partly he wanted to see what I was doing…but mostly he wanted a treat for no particular reason. Of course I gave it to him.

Author: Leslie Cook

A Protein Smoothie – A Delicious Dietary Solution

A Protein Smoothie is a great solution to a couple of dietary issues we have in our home. I’m not sure if it’s because we don’t absorb nutrients as effectively as older adults or if it’s just gender differences. There are certain nutrients I’ve never had difficulty getting plenty of, but my husband, Andy does. Protein is one. And of course, men need more than women.

Anyway, I started making a Protein Smoothie every day using Vega Plant-Based Protein and Greens, Chocolate. And I can never just leave something l like that alone. I take it as an opportunity to get more fresh veggies into us in a regular way. Here’s what I put together for us pretty much every day for lunch:

And that’s not to mention that we both have some bone density issues for which we walk like crazy, do floor exercises, and eat lots of greens. Still, we find we need a little help with calcium.

A Daily Protein Smoothie

Ingredients

- Oat Milk, 2 cups

- Vega Plant-Based Protein and Greens, Chocolate, 2 scoops

- Ice cubes, 2-1/2 cups

- Dark Cherries, frozen, unsweetened, 1/2 cup

- White Cabbage, 1/2 cup chunked

- Red Cabbage, 1/2 cup chunked

- Carrot, one large, cut in pieces

- Celery, two stalks, cut in pieces

- Beet, small-medium, cut in pieces

Process

Add all ingredients in that order to a VitaMix or other blender. Start slowly, and work up to speed. Blend for 2 minutes or until very smooth. It should make two 2-1/2 cup servings, about 20 oz. each.

By the time we finish lunch, between our Power Oatmeal and our Protein Smoothie, we’ve met most of our nutritional needs for the day. We have more of a variety for dinner. I’m not a big believer in supplements. I like to get our nutrients from food — but we do take one Centrum Silver each day as an insurance policy.

Ad me’ah v’esrim, (until 120) as some say.

Power Oatmeal — Breakfast of Champions

Power Oatmeal is a work in progress. It contributes significantly to our daily nutrition, so I continue to adjust it.

We used to enjoy “greenies” every day for breakfast, smoothies packed with greens, nuts, seeds, other veggies, and berries. Sometimes a banana or fruit in season. We enjoyed the greenies a lot, and they provided good nutrition, but one day we decided we wanted something chewier — and because it was cold outside, something warm. I thought maybe oatmeal would work for us.

Neither my husband, Andy, nor I was very enthusiastic about oatmeal, but I was sure I could make it so that we’d enjoy it. I used to make it regularly for my kids when they were small. I started off with steel-cut (Irish) oatmeal and added raisins, butter, brown sugar, some nuts, and a little fruit. That was a hit with them, but sugar and butter have not been part of my household menu for oh…at least twenty-five or thirty years.

Still, I wanted Andy to like it, and he does love his sweets, so I relented and threw some dark chocolate chips into the cooked oatmeal along with the other ingredients. Those other ingredients included raisins, nuts, seeds, and…here’s the first odd thing, extra virgin olive oil. I thought it would add the richness and satisfaction butter used to provide. Also, I always liked how Middle Easterners drizzle olive oil over everything, the added flavor and richness that comes from it. So…olive oil. Topped it all off with some fresh fruit, mostly berries, and there we had it. Version I.

Power Oatmeal Version II

After a few weeks, Andy said he liked the oatmeal and didn’t need the chips — it was sweet enough. Yay! So the chips went away. Next I turned my attention to calcium, which we both need. I tallied up what we get from our daily vitamin and daily diet and found it fell short. I doubled the amount of chia, hemp, and flax seeds and added calcium-rich sesame seeds. But we were still short.

There was one other problem. Andy sometimes has a hard time chewing some of those good greens, and when we quit the greenies (temporarily, but that’s another story), we weren’t getting enough of those into our day. So I had a thought: what if I cooked the greens into the oatmeal? With all the other flavors, I had a feeling it would be just fine. And if I chose my greens well, along with all that great nutrition, there would be a healthy dose of calcium. Collards worked well for that.

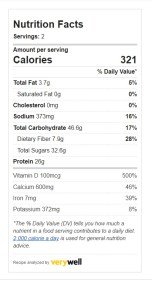

If you take a look at the current Nutrition Facts, you’ll see that the numbers show that this oatmeal dish gives us 27+ gm of protein, a good bit of iron, and enough calcium along with our daily vitamin and other foods for us to satisfy our daily requirement.

Power Oatmeal – The Recipe

And now here’s what I make every morning. It’s not for someone on a tight morning schedule — it takes me half an hour to make if I really pump and half an hour to eat. But we’re retired!

It may sound weird. But it’s good and a great nourishing (and filling) breakfast for us seniors! We don’t feel like eating again until 2:30 or so in the afternoon.

Ingredients

- Steel Cut Oats (I use Bob’s Red Mill)

- Raisins, 1/2 cup

- Salt, 1/4 tsp

- Collards, 2 large leaves, finely chopped to make 1-2 cups

- Chia, 2 TB

- Hemp, 2 TB

- Flaxseed, 2 TB

- Sesame, 2 TB

- Pears (or peaches or any in-season fruit), 2 cut up

- Strawberries, 1/2 cup cut up

- Blueberries, 1 cup

- Almonds, 24

- Walnut halves, 16

- Extra virgin olive oil, 2 TB

Process

- Put 2 cups water into a pot with a good-sized pinch of salt and the raisins. Bring to a boil.

- While the water is heating, chop the collards and add them to the pot.

- When the water comes back to a boil boil, add 1/2 cup steel-cut oats. Turn heat to simmer, put lid on pot, and cook for ten minutes.

- While the oatmeal, collards, and raisins are cooking, cut up the fruit, chop the nuts, and grind the seeds.

- When the oatmeal is finished cooking (10 minutes simmering after a boil), stir in the ground seeds.

- Empty the oatmeal/collards/raisins and seed mixture into two large bowls.

- Drizzle extra virgin olive oil generously over each dish of oatmeal.

- Add to the oatmeal with pears or peaches or any other in-season fruit — and fresh or frozen berries and blueberries.

- Top each bowl with chopped or ground nuts, depending on how much crunch you want.

- You may need to heat each bowl for a minute or two in the microwave after topping the hot oatmeal with cold and room temperature ingredients.

Now about that 2:30 pm meal…

Back to smoothies. We found that we were light on protein and needed a boost, something we could count on getting every day. I looked around for a vegan protein powder and found a delicious one, Vega Protein and Greens. 20+ grams of protein in each scoop. Perfect! Mixed with one cup each of oat milk, the “shake” gives us another 400 grams of calcium as well. And since I’m always looking for ways to boost our veggie nutrition, I of course started adding a few veggies, turning it into a smoothie — celery, carrot, beet, white cabbage and red cabbage.

This leaves me just one meal a day to think about and do something a little creative, at least until we get underway with our journeys around the country in our van. I decided not to take my Vitamix, so we’ll just enjoy a protein shake without the veggies, frothed with my new hand blender. I’ll need to figure out a delicious way to keep getting those additional veggies each day tho. Not sure that hand blender will do it.

An Ant and a Rubber Tree Plant: A Metaphor

Everyone knows an ant can’t . . . move a rubber tree plant.

This morning as I exercised, I watched an ant make its way alongside my mat. The rubber tree plant song drifted briefly through my consciousness, but then I returned my attention to the ant in its travels.

I like to do my stretching and strength exercises in the early morning by the sliding glass doors at the back of my home looking out to the wetlands. There is a pond right behind me, although these days you wouldn’t know.

I used to love watching all kinds of birds and animals visit the pond in the morning. Now a wilderness has grown up around the pond, and it is invisible to me. My viewing range is much smaller. So my attention is drawn to ongoing life happening closer to me.

This morning a tiny insect crawling just inside my sliding doors less than a foot away from me drew my attention. I was lying on the floor on my side as I watched that tiny being move across the little wooden landscape that stretched between me and the door.

To that small living being, the landscape must have seemed quite large and endless, yet the ant was making progress . . . to somewhere. I wondered if it knew where it was going?

Then I thought how immense I was next to that tiny living being. And how the ant continued its journey so fearlessly.

This is where my thoughts focused. It occurred to me that the ant may not have been fearless but oblivious. From the ant’s perspective, I am huge — so huge that I am incomprehensible, beyond imagining.

And so the ant continued on its path to wherever it was going unaware of possible danger in that moment. Was there perhaps some undefined anxiety for the ant feeling a presence it can’t begin to imagine? If an ant can imagine my enormous presence in some way, might it have the audacity to imagine that I care for it?

It occurred to me that the ant’s relationship to me mirrors my relationship to G-d. While I’m not sure that ants imagine, I know human beings do. I like to imagine that the immense force that breathes life into all being, that is all being, is One with whom relationship is possible.

Relationships aren’t fixed in space and time. They change. There has been a distance between me and divinity for most of my life. I feel as though I’ve spent too much time locked in obliviousness, anxiety, and constriction. I also feel as though I’m on a different path now. At least I hope I am. I hope at least I can manage courage like the ant.

BaMidbar: The Wilderness of Sinai |Tough Love?

The Wilderness of Sinai is the place G-d chooses to communicate to the Israelites through Moses. It is where G-d reveals Torah and repeatedly offers saving grace. For the Israelites, the wilderness is a place of wandering. It is also a place of terror and near despair.

Why does G-d choose the wilderness to speak directly to Moses and through him, to G-d’s people? And why was the wilderness the scene of revelation and saving acts? Finally, why did this story unfold in a place of hardship and terror for the Israelites?

And why did the journey extend to 40 years? According to Google Maps, the walk from Cairo to Jerusalem is about 452 miles or 148 hours on foot. With twelve-hour days, 148 hours would make the journeying time almost two weeks (12.3 days). Remember, there were kids on the journey and sheep. People needed time to set up and take down camps and find and prepare food. Oh, and yes, a desert tabernacle.

Let’s quadruple the time, giving just three hours a day to walking. Still a little under two months. Let’s add on the same number of days for stopping altogether, not traveling. Four months. The Israelites could have paused for many more months near oases and still not approached anywhere near 40 years.

Not was it possible, but why was it necessary?

Perhaps Moses was an experienced survivalist, although the Torah never describes him in that way. It’s unlikely though that many in the ragtag crowd following him were. Numbers 1:46 tells us there were 603,550 adult men, which suggests a total population of around 2.4 million. 2.4 million people including children wandering through and living off the wilderness and what they were able to bring with them when they left Egypt in great haste.

My question isn’t, “Was it possible?” It is “Why was it necessary to the story that the march from slavery to freedom happen in a brutal wilderness?” In these vast numbers? Why did a harsh desert become the place where the Israelites developed a relationship with G-d?

The Wilderness of Sinai

I always like to think of a wilderness as a place where everything is simplified, where non-essentials are stripped away. I heard the desert described once as a “mikveh,” a place of cleansing — perhaps washing away non-essentials. But I think it goes deeper than that. I suspect it’s more like tough love than gentle persuasion toward mindfulness. There is no arguing with intense temperatures, thirst, and starvation.

Read this description from Dr. Claude Mariottini of what the Israelites faced as they wandered for forty years through the Wilderness of Sinai (more available by clicking on the link):

“In the Sinai Peninsula, most of the land is devoid of water and vegetation, except in oases and wadis, dry river beds that may be filled with water during the winter flood. The wilderness was a harsh and inhospitable area.

“Because of the nature of the terrain, the Israelites faced many problems posed by life in the wilderness. They experienced {a} lack of food and water, diseases, earthquakes, snakes, scorpions, and attacks from enemy tribes. The Bible indicates that the situation in the wilderness of Sinai was inhospitable…”

…הַמּוֹלִ֨יכְךָ֜ בַּמִּדְבָּ֣ר ׀ הַגָּדֹ֣ל וְהַנּוֹרָ֗א נָחָ֤שׁ ׀ שָׂרָף֙ וְעַקְרָ֔ב וְצִמָּא֖וֹן אֲשֶׁ֣ר אֵֽין־מָ֑יִם…

…Who led you through the great and terrible wilderness with its seraph*seraph Cf. Isa. 14.29; 30.6. Others “fiery”; exact meaning of Heb. saraph uncertain. Cf. Num. 21.6–8. serpents and scorpions, a parched land with no water in it…

Deut. 8:15

Even in slavery, the Israelites accessed a richer diet than in the desert:

וַיֹּאמְר֨וּ אֲלֵהֶ֜ם בְּנֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֗ל מִֽי־יִתֵּ֨ן מוּתֵ֤נוּ בְיַד־יְהֹוָה֙ בְּאֶ֣רֶץ מִצְרַ֔יִם בְּשִׁבְתֵּ֙נוּ֙ עַל־סִ֣יר הַבָּשָׂ֔ר בְּאׇכְלֵ֥נוּ לֶ֖חֶם לָשֹׂ֑בַע כִּֽי־הוֹצֵאתֶ֤ם אֹתָ֙נוּ֙ אֶל־הַמִּדְבָּ֣ר הַזֶּ֔ה לְהָמִ֛ית אֶת־כׇּל־הַקָּהָ֥ל הַזֶּ֖ה בָּרָעָֽב׃ {ס}

The Israelites said to them, “If only we had died by the hand of יהוה in the land of Egypt, when we sat by the fleshpots, when we ate our fill of bread! For you have brought us out into this wilderness to starve this whole congregation to death.”

Ex. 16:3

Existential terror

As Dr. Mariottini points out, the Israelites were poorly prepared for a forty-year journey in this environment. And it’s not quite “a band of brothers” fighting for their survival. It’s 2.4 million people, a “mixed multitude” or ragtag group (וְגַם־עֵ֥רֶב רַ֖ב עָלָ֣ה אִתָּ֑ם), many vulnerable. They travel through dry, rocky, unforgiving terrain where they were as likely to be prey as predators. The Golden Calf episode fully reveals their state of existential terror as they experience abandonment in a hostile environment. It is revealed once again when the spies return from Canaan:

וַיִּלֹּ֙נוּ֙ עַל־מֹשֶׁ֣ה וְעַֽל־אַהֲרֹ֔ן כֹּ֖ל בְּנֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֑ל וַֽיֹּאמְר֨וּ אֲלֵהֶ֜ם כׇּל־הָעֵדָ֗ה לוּ־מַ֙תְנוּ֙ בְּאֶ֣רֶץ מִצְרַ֔יִם א֛וֹ בַּמִּדְבָּ֥ר הַזֶּ֖ה לוּ־מָֽתְנוּ׃

All the Israelites railed against Moses and Aaron. “If only we had died in the land of Egypt,” the whole community shouted at them, “or if only we might die in this wilderness!”

וְלָמָ֣ה יְ֠הֹוָ֠ה מֵבִ֨יא אֹתָ֜נוּ אֶל־הָאָ֤רֶץ הַזֹּאת֙ לִנְפֹּ֣ל בַּחֶ֔רֶב נָשֵׁ֥ינוּ וְטַפֵּ֖נוּ יִהְי֣וּ לָבַ֑ז הֲל֧וֹא ט֦וֹב לָ֖נוּ שׁ֥וּב מִצְרָֽיְמָה׃

“Why is יהוה taking us to that land to fall by the sword? Our wives and children will be carried off! It would be better for us to go back to Egypt!”

וַיֹּאמְר֖וּ אִ֣ישׁ אֶל־אָחִ֑יו נִתְּנָ֥ה רֹ֖אשׁ וְנָשׁ֥וּבָה מִצְרָֽיְמָה׃

And they said to one another, “Let us head back to Egypt.”

Num. 14:2-4

Imagining ourselves into the wilderness story

The Wilderness of Sinai is a harsh environment. It is not like the Garden of Eden, a place of compassionate abundance. The wilderness is also a long way from the place in which most of us live today. Not many of us have had to find a way to survive in a desert wilderness. We haven’t had to survive in a place where food and water and the building blocks of shelter are scarce. We shop at grocery stores rather than compete for scarce resources. Imagine the intense competition for basic resources with 2.4 million people in a desert trying to stay alive.

Is there a way to imagine ourselves into the reality of that wilderness experience and see it as much an expression of love and compassion as the story of Creation, chapters 1-3 of Genesis?

The wilderness as predator

Human beings have basic survival needs that they share with all other animals. As National Geographic points out, “Animals need food, shelter from weather and predators, water, and a place to raise young.”

Abraham Maslow in a 1943 article in Psychological Review titled “A Theory of Human Motivation” points to a hierarchy of needs among humans. Survival is the most basic. Without fulfilling basic survival needs, there is no possibility of moving up the hierarchy to love and to self-transcendence. Survival is primary.

Yet according to the Torah story, G-d brings a crowd into the wilderness, millions. The demands on the minimalist eco-system that is the desert would have been unsupportable. If the Israelites can’t even provide for their basic survival needs, how can they ever move beyond them to the future promised them? The wilderness preys on their future.

Yet G-d brings the Israelites to this place and keeps them in it for 40 years.

The wilderness as saving vessel

As in the Noah’s Ark story, the saving vessel is an environment calculated to challenge the possibility of cohabitation. It brings those within it to the breaking point and beyond in their relationships.

Also like the Noah’s Ark story, the Israelites don’t know where they are going. As slaves for four hundred years, they had no opportunity to see the Land promised to their ancestors. All this massive ragtag group knows is the overcrowded, fragile environment in which they find themselves, an environment that is both no-place and every-place. This present terrifying, harsh, and impossibly crowded moment is all they have.

Yes, G-d is there with the Israelites, offering moments of grace, providing water and manna — but utter dependence on another being for survival can also be terrifying.

The stage is set for complete social and spiritual catastrophe. How do we find love and compassion in this story of the post-slavery wandering in the wilderness?

Wilderness training

When he was thirteen, my younger son went to Outward Bound for three weeks of wilderness experience. For most of the time, he was with a group of others his age led by experienced guides. For two days he was solo.

I could tell from his letters that he was unhappy when he started out, away from home with people he didn’t know, carrying a 50-pound pack through the mountains, learning survival skills, and confronting physical challenges like rappelling off the walls of glaciers.

By the time he completed the trip, though, he appreciated the experience as the most powerful and transformative of his life to that point. As he approaches 5 decades of life, I believe he still looks back on it as one of a handful of life-changing experiences.

Outward Bound describes its programs this way: “Outward Bound programs inspire young people and adults to stretch beyond their perceived abilities. In balancing responsibility, risk and reward, and in learning to act boldly, deliberately, and with compassion, students experience profound growth and lasting change.”

Here’s how they explain the choice of place for their expeditions:

- Outdoor environment simplifies as it inspires.

- Novel physical settings require new ways of thinking and acting.

- Physical remoteness emphasizes interdependence and self-reliance.

- Unplugging from connected lifestyles promotes focus and perspective.

In the group framework, “Students learn to trust each other’s strengths and support each other’s needs.” Their solo time teaches self-reliance and “creates space for mindful learning from experience.”

The wilderness experience simultaneously teaches interdependence and self-reliance, learning to depend on and cooperate with a group of diverse people while challenging one’s own abilities and gaining confidence and realistic self-appreciation.

Finally, Outward Bound says of its program, “These skills are infinitely transferable and support students’ successes at work and school, and in their careers, families and communities.”

Building community: self-reliance and caring cooperation

The Israelites weren’t preparing for success in their careers but rather for the often harsh conditions of life. And not just any life. Their lives would be dedicated to building a nation with a social culture that emphasized compassionate, righteous, moral behavior, a representation in the human realm of the love and compassion of creation. The moral fabric of the universe demanded a corresponding moral response from human beings who benefitted from it.

The Israelites had to forge more than a cohesive nation that would stand up to assault from starvation and thirst, diseases, earthquakes, snakes, scorpions, and enemy tribes. They had to build a moral nation, a compassionate nation, one based on trust and faith in a loving G-d. Their task required strength and persistence even in the face of unimaginable tragedy.

Each individual needed to test his or her own strength, endurance, and resourcefulness — but at the same time learn to depend on those around them. They had to learn of and appreciate each other’s unique skills and abilities…discover their own and others’ vulnerabilities, and support the vulnerable. Their ability to survive and grow beyond survival to create a righteous society depended on caring cooperation in the group as a whole. And this lesson in compassionate cooperation had to hold up under the most trying circumstances when resources were few and human beings most likely to focus only on their own selfish survival needs.

In evolutionary terms, “‘Selfish’ genes that don’t cooperate don’t survive. A more fitting view is that there are evolutionary limits to selfishness. Nature dooms all that damages what it depends on.”

Beyond community: an interdependent web of being

There was another aspect to the Israelites’ wilderness experience beyond developing self-reliance and building compassionate, cooperative relationships with their fellow travelers. The Israelite universe was built on relationships within and between three realms: humanity, the rest of creation, and Transcendence. It was an interdependent universe, a web of being and meaning.

Just as the Israelites had to learn in an environmental pressure cooker to develop and maintain righteous relationships with their neighbors, other living beings, and their habitat, they had to learn how to relate to Transcendence, to their G-d.

Any relationship requires reciprocal trust. The wilderness environment presented many challenges to trust on all sides. The story tells us how many times the Israelites disappointed G-d. There were also inevitable moments when hope failed and disabling despair threatened to set in for the Israelites. In those moments, they had to dig deep and find faith that G-d created everything with a plan and the plan included them.

Trust, the foundation of faith

Trust isn’t inevitable or easy, even in a G-d who sends an earthly leader to save the people from grinding slavery and who provides food, water, and shelter at critical moments during their journey. What if G-d isn’t there the next time? Disappears? Perhaps trust comes when there is nothing else you can do but trust.

When you weep as you bury the precious seed, you have to find it in yourself to trust you will rejoice as you come home carrying your sheaves (from Shir Ha-Ma’alot, prelude to Birkat Ha-Mazon). If you rely on the harvest to survive, you must trust in outcomes or you’ll never put that precious seed into the ground.

It turns out that nurturing and maintaining faith and hope even in the most challenging and terrifying circumstances is essential for self-preservation. Faith insists there is a bigger picture even when you don’t know what it is.

Faith in the infinite tensile strength of interdependence

So back to the starting questions: Why was it necessary to the story that the march from slavery to freedom happen in a brutal wilderness? And in these vast numbers? How is the Israelites’ wilderness experience an expression of G-d’s love and compassion?

The wilderness experience was necessary to strip away everything non-essential, leaving the Israelites to experience the infinite tensile strength of the interdependent relationships that would move them forward into the future. Their numbers in the midst of scarcity intensified the pressure on forging those relationships and maintaining them for the sake of group survival.

G-d’s saving grace in the midst of impossibility provided the Israelites repeated opportunities to learn trust and build faith. They would need it as they moved forward. Yet faith often faltered, and G-d had to repeat the lesson.

The Wilderness and the Garden…the same precious gift

The Garden and the Wilderness are the same gift: an opportunity to experience the interconnection of all being, between human beings, the rest of creation, and divinity. Interconnection persists even in the most challenging circumstances. It just is. And when the Israelites experienced it in moments of full awareness in the wilderness, perhaps they saw themselves as an inextricable and eternal part of a grand and beautiful design. And perhaps that gave them courage to move forward.

The Breath of All Life …Our Connection

I first published this post June 25, 2020, then withdrew it. I don’t remember exactly why. Perhaps there was something that made me uncomfortable as I thought more about these themes. Perhaps it just seemed too long or needed editing. But my blog is really a thought-journal for me. That’s why I decided to republish now, a year later, to make it part of my ongoing record.

The Breath of All Life . . . Nishmat kol Chai in Hebrew . . . has always been one of my favorite prayers. G-d’s breath animates all life. All life sings its praise and appreciation just by being. The prayer speaks to a unity of being, a reciprocity of being, relationship.A few weeks ago I started writing a post about a story in the first three chapters of Genesis. In these chapters, G-d brings created beings to life by breathing into them. It was about the unity of all being expressed in this image of G-d’s breath. It was also about unique capabilities of human beings. These capabilities make them the best candidates for the job of caring for the world G-d created and the living beings in it. And of course it was about what all this says about the relationship between human beings and nonhuman animals.

This insight into the unity of all being is not exclusive to the Hebrew Bible. I suspect it is a basic truth known to humanity since we began to think and imagine, our unique human ability. The Navajos express these insights in this direct way in The Navajo Fundamental Laws of the Dine’. Read this section on Natural Law of the Dine’: “All creation, from Mother Earth and Father Sky to the animals, those who live in water, those who fly and plant life, have their own laws and have rights and freedom to exist; and the Dine’ have a sacred obligation and duty to respect, preserve and protect all that was provided, for we were designated as the steward of these relatives through our use of the sacred gifts of language and thinking…”

Until modern times, the insight into the unity of all being has been considered part of the world of faith and myth. Today, though, some are exploring deconstructing the artificial wall between faith and science. We can view them as different in process and form of expression but not necessarily content. As Neil de Grasse Tyson says, “We are all connected; To each other, biologically. To the earth, chemically. To the rest of the universe atomically…We are in the universe and the universe is in us.”

As I worked on my post, Covid-19 dragged on with its devastating symptoms that make it so difficult to breathe. Masks proliferated — or were in scarce supply — with their filters and breathing vents. My sister died. Although it wasn’t Covid-19 that caused her death, we originally thought it was because she reported difficulty breathing. Weeks of protests began when George Floyd died crying out, “I can’t breathe,” as a police officer pushed his knee down on his neck. I am more aware than ever that breath is the great unifier of all life. Everything that lives breathes, humans, nonhuman animals, plants, trees, the planet, the universe itself. Without breath, there is death.

The idea that G-d animates all being with G-d’s breath, that all being is sacred, took on the nuance of this moment in time and history. And my post took shape differently than I originally planned. The fundamentals are the same, though. So while my post isn’t directly about Covid-19, my sister’s death or George Floyd’s murder by suffocation and the protests that followed, those events were inevitably in my mind as I thought and wrote.

Unity of Being

When animism was the dominant belief system, human norms and values had to take into consideration the outlook and interests of a multitude of other beings, such as animals, plants, fairies and ghosts…The Agricultural Revolution seems to have been accompanied by a religious revolution. Hunter-gatherers picked and pursued wild plants and animals, which could be seen as equal in status to Homo sapiens.

The fact that man hunted sheep did not make sheep inferior to man, just as the fact that tigers hunted man did not make man inferior to tigers. Beings communicated with one another directly and negotiated the rules governing their shared habitat. In contrast, farmers owned and manipulated plants and animals, and could hardly degrade themselves by negotiating with their possessions. Hence the first religious effect of the Agricultural Revolution was to turn plants and animals from equal members of a spiritual round table into property. ~ Prof. Yuval Noah Harari in Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

These words had a profound effect on me when I first read them. They expressed an intuition I had that I was not yet able to form into words. They began to shape my current biblical study project. We see this idea of equality of being expressed “in the beginning,” in the first words of Genesis. Before G-d’s word, there is G-d’s breath. G-d’s word differentiates being, but G-d’s breath brings life to all, is in all. All beings are sacred.

In the biblical story, we are part of a sacred living unity through the breath (ר֨וּחַ) of G-d. There is a trilogy of words associated with this idea:

- nefesh (נֶ֥פֶשׁ – soul, or better, living, breathing being)

- hayyim, hayah (חַיִּ֑ים ,חַיָּֽה – life, living being)

- ruach (ר֨וּחַ – breath, wind, breeze, sometimes translated soul or spirit)

When G-d begins to create, G-d’s breath moves across the water. It does the same when it renews creation after the flood:

בְּרֵאשִׁ֖ית בָּרָ֣א אֱלֹהִ֑ים אֵ֥ת הַשָּׁמַ֖יִם וְאֵ֥ת הָאָֽרֶץ׃

When G-d began to create heaven and earth—

וְהָאָ֗רֶץ הָיְתָ֥ה תֹ֙הוּ֙ וָבֹ֔הוּ וְחֹ֖שֶׁךְ עַל־פְּנֵ֣י תְה֑וֹם וְר֣וּחַ אֱלֹהִ֔ים מְרַחֶ֖פֶת עַל־פְּנֵ֥י הַמָּֽיִם׃

the earth being unformed and void, with darkness over the surface of the deep and a wind from G-d sweeping over the water— (Gen. 1:1-2)

וַיִּזְכֹּ֤ר אֱלֹהִים֙ אֶת־נֹ֔חַ וְאֵ֤ת כָּל־הַֽחַיָּה֙ וְאֶת־כָּל־הַבְּהֵמָ֔ה אֲשֶׁ֥ר אִתּ֖וֹ בַּתֵּבָ֑ה וַיַּעֲבֵ֨ר אֱלֹהִ֥ים ר֙וּחַ֙ עַל־הָאָ֔רֶץ וַיָּשֹׁ֖כּוּ הַמָּֽיִם׃

G-d remembered Noah and all the beasts and all the cattle that were with him in the ark, and G-d caused a wind to blow across the earth, and the waters subsided. (Gen. 8:1)

The commonality of vocabulary signifies commonality of meaning. Nonhuman animals, like humans, are basar (בָּשָׂ֣ר – body, flesh, even “carcass”). When flesh is animated by the breath of G-d, ruach, that flesh becomes nefesh, a whole, breathing, living being. The Hebrew word nefesh refers equally throughout the biblical text to fish, birds, land animals and human beings:

וַיִּיצֶר֩ יְהוָ֨ה אֱלֹהִ֜ים אֶת־הָֽאָדָ֗ם עָפָר֙ מִן־הָ֣אֲדָמָ֔ה וַיִּפַּ֥ח בְּאַפָּ֖יו נִשְׁמַ֣ת חַיִּ֑ים וַֽיְהִ֥י הָֽאָדָ֖ם לְנֶ֥פֶשׁ חַיָּֽה׃

the LORD G-d formed man from the dust of the earth. He blew into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living being. (Gen. 2:7)

כֹּ֡ל אֲשֶׁר֩ נִשְׁמַת־ר֨וּחַ חַיִּ֜ים בְּאַפָּ֗יו מִכֹּ֛ל אֲשֶׁ֥ר בֶּחָֽרָבָ֖ה מֵֽתוּ׃

All in whose nostrils was the merest breath of life, all that was on dry land, died. (Gen. 7:22)

Through breath, all being is interconnected, a unity. All of life, plants and animals, the heavens and the earth, along with humans, sits at the spiritual round table. This is a world in which it’s possible to encounter G-d walking in the Garden at a “breezy” time of day. It is a time and space when G-d’s breath (ר֨וּחַ – ruach) fills the air:

… וַֽיִּשְׁמְע֞וּ אֶת־ק֨וֹל יְהוָ֧ה אֱלֹהִ֛ים מִתְהַלֵּ֥ךְ בַּגָּ֖ן לְר֣וּחַ הַיּ֑וֹם

They heard the sound of the LORD G-d moving about in the garden at the breezy time of day; (Gen. 3:8)

So Genesis describes a world in which all of life is sacred, every creature a sacred being brought to life with the breath of G-d. Our profound connection to all being is the basis of faith for many, and respect for life is a corollary of that faith. It is a recognition of G-d’s breath in all, an understanding that we all sit as equals at the spiritual round table.

Diversity Of Being

Modern cosmology reflects an interaction of opposites with life originating in the balance between them, moving toward increasing diversity and complexity: gravity pulls inward toward density, and dark energy pushes outward toward expansion of the universe and increasing complexity of structures. Life is a particularly intricate natural structure that arises under the right circumstances, between order and chaos.

The Hebrew Bible reveals this same insight by presenting opposite ideas and telling a story that weaves in and out between them, seeking a balance. The idea of unity and equality of all being is one half of a set of opposites. It is in a delicate yet powerful interaction with another idea, diversity and particularism. Just as Genesis 1-3 tells a story of sacred unity, all being animated by the breath of G-d, it also tells a story of sacred diversity, created with G-d’s word. These two ideas, unity and diversity, are opposite but not oppositional, not a binary. They represent an interaction. Life happens in the balance between the opposites.

Looking more deeply at the diversity theme in Genesis 1-3, we see that Genesis tells its story by describing a six-day process crowned with a seventh day of rest. In this process, creating is diversifying as God separates and distinguishes parts of creation. Each day God brings a different part of the world into being, more “structures,” to use the scientific term. The biblical word that signifies differentiation is from the root בָּדל (b-d-l, separate):

וַיַּ֧רְא אֱלֹהִ֛ים אֶת־הָא֖וֹר כִּי־ט֑וֹב וַיַּבְדֵּ֣ל אֱלֹהִ֔ים בֵּ֥ין הָא֖וֹר וּבֵ֥ין הַחֹֽשֶׁךְ׃

G-d saw that the light was good, and G-d separated the light from the darkness. (Gen. 2:4)

The thought that there is a unity of all being is a basic insight humans are privileged to have, that they access through a process of imagination. But the diversity of the cosmos, the diversity of creation, is an equally compelling, counterbalancing insight. All beings are not the same. We don’t look the same, think the same, act the same, or have the same gifts and talents. Each part of creation, each species, each individual being, has its own unique characteristics perfectly suited to itself. It must — otherwise it would not be able to survive in its moment in time and space.

Many years ago I learned a beautiful prayer, Nishmat Kol Chai, “The Breath of All Living (praises your name)…” I once received a gift, a framed version of it, calligraphed by a friend of mine. I’ll share the words that make up the body of the prayer:

Though our mouths were filled with song as the sea

And our tongues with joy as the multitude of its waves

And our lips with praise as the wide expanse of the firmament

Though our eyes were radiant as the sun and the moon

And our hands were spread forth like the eagles of heaven

Though our feet were swift as hinds

Yet should we be unequal to thanking Thee

O Lord our G-d and the G-d of our fathers

For one minutest measure of the kindness Thou hast shown

Unto our fathers and unto us.

The imagery of this beautiful prayer struck my imagination. This is a liturgical hymn to creation that picks up on the biblical theme of sacred diversity. It is a song that reflects on our beautiful particularity, each individual, each part of creation, each species, with its own song of praise to sing. “The breath of all living,” of every living being, nishmat kol chai, sings a song of praise and joy, each living being in its own unique way, simply by living according to its nature. “All living” incorporates not only humans but the natural environment and nonhuman animals. What an extraordinary image — every living being, all life, praises G-d just by living in the world and being its unique self.

Browsing the internet one day, I found this beautiful version of the prayer. It made me wish I could express myself this way. But I reminded myself that just as each species is unique, so is each individual within each species. The diversity of all being like its unity is limitless, infinite: The Breath of All Life – “Nishmat Kol Chai,” Joey Weisenberg and the Hadar Ensemble (featuring Deborah Sacks and Mattisyahu Brown)

And there’s this: “Song of the Grasses”, lyrics by Naomi Shemer. I chose this version because it includes the translation with the music. There are many beautiful renditions in YouTube, though. Search on Shirat Ha-Asavim or “Song of the Grasses”: Song of the Grasses, sung here by Shuli Rand.

But in case you don’t stop to listen to this beautiful music, here is the English translation of “The Song of the Grasses”:

Do know that each and every shepherd has his own tune? Do know that each and every grass has its own poem? And from the poem of the grasses, a tune of a shepherd is made. How beautiful, how beautiful and pleasant to hear their poem! It is very good to pray among them and to serve the Lord with joy. From the poem of the grasses, the heart is filled and yearns. And when the poem causes the heart to fill and to yearn to the Land of Israel, a great light is drawn and goes from the Land’s holiness upon it. And from the poem of the grasses a tune of the heart is made.

The Necessity of Freedom – The Exodus

Life develops in the space between oppositional motifs: unity and diversity; undifferentiated darkness and void and a dazzling array of differentiated being; freedom of choice and determinism. The story in the Hebrew Bible unfolds between opposites.

There are corollaries to these parallel ideas of unity and diversity. One of these is the necessity of freedom. The songs of praise that life sings can only be uttered from within a state of freedom, a space where each is free to live its life, expressing itself in its own unique way.

The Hebrew Bible places a high value on freedom. Why? Because in being who we are, we serve creation. If we are G-d-believers, we serve the G-d of creation according to our nature. But how can any part of creation fulfill its potential, serve creation, if it is not free?

The story of the Exodus elaborates the freedom theme. The Israelites, who had to become free in order to serve their G-d, the G-d of creation, are emblematic. They even had to be freed from their slave mentality by wandering through the desert for forty years! Praising G-d with their unique song required freedom for every individual, freedom in body and mind.

בְּהוֹצִֽיאֲךָ֤ אֶת־הָעָם֙ מִמִּצְרַ֔יִם תַּֽעַבְדוּן֙ אֶת־הָ֣אֱלֹהִ֔ים עַ֖ל הָהָ֥ר הַזֶּֽה׃

And when you have freed the people from Egypt, you shall worship G-d at this mountain. (Ex. 3:12)

But the freedom theme doesn’t apply only to humans. Nishmat Kol Chai echoes the biblical text in extending freedom to other beings. This verse from Exodus ordains the Sabbath observance:

וְי֙וֹם֙ הַשְּׁבִיעִ֔֜י שַׁבָּ֖֣ת ׀ לַיהוָ֣ה אֱלֹהֶ֑֗יךָ לֹֽ֣א־תַעֲשֶׂ֣֨ה כָל־מְלָאכָ֡֜ה אַתָּ֣ה ׀ וּבִנְךָֽ֣־וּ֠בִתֶּ֗ךָ עַבְדְּךָ֤֨ וַאֲמָֽתְךָ֜֙ וּבְהֶמְתֶּ֔֗ךָ וְגֵרְךָ֖֙ אֲשֶׁ֥֣ר בִּשְׁעָרֶֽ֔יךָ

but the seventh day is a sabbath of the LORD your G-d: you shall not do any work—you, your son or daughter, your male or female slave, or your cattle, or the stranger who is within your settlements. (Ex. 20:10)

Why does the verse specifically mention cattle, a nonhuman animal? Because just as the Israelites required freedom from slavery to worship G-d in their unique way, all creatures require freedom to praise G-d through their natural and unique way of being in the world. Freedom from labor one day a week for all living in the Israelite world applies emblematically to all being.

Another corollary to the contrasting themes of unity and diversity of being is that freedom has limits. Some of these limits are simply a natural part of living in the world. We all have to sustain ourselves, do the work of living. It’s not realistic to imagine we can be totally free — but the Sabbath provides a space in time for freedom. It extends to cattle, by extension to all domestic (working) animals.

There are other limits on freedom. Exercising one’s freedom can impact the expression of another’s, even completely eliminate it. If every living being is part of a whole, then if any individual being is unfree, wounded, abused or diminished, it necessarily affects the whole — and if any neglects consideration of “the other” in enjoying personal freedom, it impacts the whole.

The freedom theme unfolding between the contrasting themes of equality of being and free expression of diversity points to the need for stewardship. This steward’s job is to make certain that each part of the whole gets its fair share of space, its freedom within limits. The Hebrew Bible captures this idea with the image of a gardener.

Limits and the Necessity of Ethics – Tending the Garden

The job assignment for the human being is gardener in creation, which the first chapters of Genesis tell us:

וַיִּקַּ֛ח יְהוָ֥ה אֱלֹהִ֖ים אֶת־הָֽאָדָ֑ם וַיַּנִּחֵ֣הוּ בְגַן־עֵ֔דֶן לְעָבְדָ֖הּ וּלְשָׁמְרָֽהּ׃

The LORD G-d took the man and placed him in the garden of Eden, to till it and tend it. (Gen. 2:15)

What a beautiful idea, that our purpose as human beings, our job, is to tend and nurture the garden of creation. But what does that mean? What does a gardener do? Of course a gardener tends the garden in such a way that everything in it grows to full potential, yields a rich harvest. If the breath image tells us of unity and equality of being, the garden image tells us of diversity. Creation is a vast array of unique beings, and our job as gardeners is to ensure that conditions are optimal for all to grow to fruition. This involves nurturing not only everything growing in the garden but the earth itself.

Yes, it is a beautiful, calming, peaceful image, an imagined reality that expresses a unity of all being — and an equality of being. All beings are vegan. There is no death. G-d’s breath is in all being, all living creatures.

But the creation story in Genesis 1-3 doesn’t leave us there. There is a real-life challenge embedded in the idea of gardening. Gardens grow weeds that choke out other growth, and plants need pruning to fulfill their potential. That, like human beings at the top of the food chain, is an objective reality.

So this image of human beings as gardeners points to the necessity of making value judgments and decisions and choices. Why are human beings given this task in creation? What qualifies us for this job? And here I return to the idea of the uniqueness of each living being, our sacred diversity.

Our Job Qualification: Imagination — A Technology for Making Choices Between the Opposites

“Fiction has enabled us not merely to imagine things, but to do so collectively. We can weave common myths such as the biblical creation story, the Dreamtime myths of Aboriginal Australians, and the nationalist myths of modern states. Such myths give Sapiens the unprecedented ability to cooperate flexibly in large numbers. Ants and bees can also work together in huge numbers, but they do so in a very rigid manner and only with close relatives. Wolves and chimpanzees cooperate far more flexibly than ants, but they can do so only with small numbers of other individuals that they know intimately.

Sapiens can cooperate in extremely flexible ways with countless numbers of strangers…Ever since the Cognitive Revolution, Sapiens have thus been living in a dual reality. On the one hand, the objective reality of rivers, trees and lions; and on the other hand, the imagined reality of gods, nations and corporations. As time went by, the imagined reality became ever more powerful, so that today the very survival of rivers, trees and lions depends on the grace of imagined entities such as the United States and Google.” ~ Prof. Yuval Noah Harari in Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind (The Tree of Knowledge)

The Hebrew Bible points to unique particularities within a unity and equality of being. There are three environments, each differentiated from the other: the seas, the heavens and dry land. A dazzling variety of living beings populates each environment. Nishmat Kol Chai reflects the idea that each different part of creation, each living being, sings its own song of praise.

But what specifically, makes human beings unique? What makes us a good choice for the job the text assigns us, that of the gardener in creation? How does that fit with the instruction to “rule” and “subdue,” and what do those words mean in this context? What does it mean to be “in the image” of G-d?

Harari provided me with the first answer that really resonated with me. What differentiates human beings from other living beings is our ability to imagine, to create pretenses or stories and to persuade others to believe them. This ability in turn enables large-scale, flexible cooperation. It is an objective reality that we dominate creation — and it results from our unique abilities. Creating imagined realities and persuading others to share in them so we can cooperate in a unique way brought us to the top of the food chain.

The Hebrew Bible describes an objective reality when it sets human beings to rule creation. The text itself, though, the story it tells, is an imagined reality.

So what, exactly, is the imagined reality the Hebrew Bible presents with regard to our relationship to other beings? How are we to understand the many passages representing violence and bloodshed, hierarchies and dominance? Do the words “rule” and “subdue” support claims that we are meant to dominate other beings? That we are superior to them?

What Does It Mean to “Rule” and “Subdue”?

To get a glimpse of textual nuance even in what seem to be direct statements of hierarchy and domination, I’d like to take a look at the vocabulary in three verses, Genesis 1:26-28. These verses are often cited to justify hierarchies and human dominance — over nature, over other living beings, even of one group of humans over another:

וַיֹּ֣אמֶר אֱלֹהִ֔ים נַֽעֲשֶׂ֥ה אָדָ֛ם בְּצַלְמֵ֖נוּ כִּדְמוּתֵ֑נוּ וְיִרְדּוּ֩ בִדְגַ֨ת הַיָּ֜ם וּבְע֣וֹף הַשָּׁמַ֗יִם וּבַבְּהֵמָה֙ וּבְכָל־הָאָ֔רֶץ וּבְכָל־הָרֶ֖מֶשׂ הָֽרֹמֵ֥שׂ עַל־הָאָֽרֶץ׃

And G-d said, “Let us make man in our image, after our likeness. They shall rule the fish of the sea, the birds of the sky, the cattle, the whole earth, and all the creeping things that creep on earth.”

וַיִּבְרָ֨א אֱלֹהִ֤ים ׀ אֶת־הָֽאָדָם֙ בְּצַלְמ֔וֹ בְּצֶ֥לֶם אֱלֹהִ֖ים בָּרָ֣א אֹת֑וֹ זָכָ֥ר וּנְקֵבָ֖ה בָּרָ֥א אֹתָֽם׃

And G-d created man in His image, in the image of G-d He created him; male and female He created them.

וַיְבָ֣רֶךְ אֹתָם֮ אֱלֹהִים֒ וַיֹּ֨אמֶר לָהֶ֜ם אֱלֹהִ֗ים פְּר֥וּ וּרְב֛וּ וּמִלְא֥וּ אֶת־הָאָ֖רֶץ וְכִבְשֻׁ֑הָ וּרְד֞וּ בִּדְגַ֤ת הַיָּם֙ וּבְע֣וֹף הַשָּׁמַ֔יִם וּבְכָל־חַיָּ֖ה הָֽרֹמֶ֥שֶׂת עַל־הָאָֽרֶץ׃

G-d blessed them and G-d said to them, “Be fertile and increase, fill the earth and master it; and rule the fish of the sea, the birds of the sky, and all the living things that creep on earth.” (Gen. 1:26-28)

In these verses, G-d tells human beings they are to “rule” creation — and in case we missed it in vs. 26, we read it again in vs. 28 with emphasis — to “master” creation. And sandwiched between this set of statements, in vs. 27, we learn “G-d created man in His image, in the image of G-d He created him; male and female He created them.” The text seems to tell us that the phrase “in the image of G-d” has relevance to our job assignment, in particular the tasks of ruling and subduing.

I explored the meaning of these phrases in other posts: Creation — Equality of Being, Abundance for All, and Everything Has a Place, Everything in its Place. Here, though, I just want to focus on three terms.

Va-Yirdu (וְיִרְדּוּ֩), translated “rule,” from verses 26 and 28, comes from the root y-r-d, which means go down, descend. This imagery contrasts with what most of us think of when we hear the English word, “rule,” which connotes superiority, being higher. The nuance in the Hebrew word gives it a different feeling. Humans are G-d’s representatives in creation — they go “down” from the imagined place where they receive G-d’s instruction. They are part of creation, home rule, in a sense, representing G-d. As part of the local environment, they will feel connected to it, feel its pain. Their fate connects to its fate.

V’kiv-shu-ha (וְכִבְשֻׁ֑הָ), translated “subdue,” from verse 28, contrasts with another word-picture in Gen. 1:25, רֶ֛מֶש (remes – creeping, moving, swarming, crawling creatures):

וַיַּ֣עַשׂ אֱלֹהִים֩ אֶת־חַיַּ֨ת הָאָ֜רֶץ לְמִינָ֗הּ וְאֶת־הַבְּהֵמָה֙ לְמִינָ֔הּ וְאֵ֛ת כָּל־רֶ֥מֶשׂ הָֽאֲדָמָ֖ה לְמִינֵ֑הוּ וַיַּ֥רְא אֱלֹהִ֖ים כִּי־טֽוֹב׃

G-d made wild beasts of every kind and cattle of every kind, and all kinds of creeping things of the earth. And G-d saw that this was good. (Gen. 1:25)

As we know from a number of verses in the Torah, those creeping, swarming beings are essentially uncontrollable. In fact, the text compares human beings with swarming creatures in contexts where they seem to be similarly uncontrollable. Subdue cannot, therefore, mean control or dominate. It cannot mean forcing other beings into a mode contrary to their natures, a “perfect” arrangement. It also can’t represent human superiority over other living beings, that is, a hierarchy of being.

Instead “subdue” suggests to me that human beings as gardeners exercise their unique capability. According to Harari, this means our ability to create an imagined reality. That imagined reality brings us closer to a world in which all of life sits at the spiritual round table. All living beings participate as equals in a unity of being expressed in freedom, justice and compassion. I think this is how the phrase “image of G-d” clarifies the meaning of “rule” and “subdue.”

B’tzalmo (בְּצַלְמ֔וֹ) means “in the image.” With this phrase, we know immediately we are in the realm of an imagined reality. We read, “…in the image of G-d He created him; male and female He created them.” How can it be that together, male and female are created in the image of G-d? That G-d is simultaneously male and female? Why bring this imagery now, between two statements that seem rather to be about humans “ruling” and “subduing” creation?

The male / female imagery implies a physical resemblance between humans and G-d. The paradoxical nature of the image indicates a symbolic meaning, perhaps picking up on the theme of diversity in unity. But there is more. Sandwiched between two directives to human beings that they are to “rule” and “subdue” is the phrase, “in the image.” This placement is not accidental. It clarifies the meaning of “rule” and “subdue.”

How so? Gardening, the job we were hired to perform in creation, is a task that requires value judgments and ethical decision-making. What if “in the image” refers to the unique characteristic we have as human animals, the ability to live in a dual reality? As Harari points out, we humans are unique in that we live in “the objective reality of rivers, trees and lions; and on the other hand, the imagined reality of gods, nations and corporations.”

Ethics — Between the Poles

Ethics reside in the realm of imagined reality, something else Harari points to in Sapiens. As he says, there is no objective evidence for any moral system. Yet gardens require a gardener who can make value judgments. On what basis do we make value judgments? How do we make decisions in physical reality about what is taking more than its share of space and nourishment, what needs more? What contributes to the whole and and what puts it at risk? What lives and what dies? We make those decisions in the framework of ethical codes.

Effectively, through its position in the text, “in the image” defines what it means to “rule” and “subdue.” As gardeners, as we rule and subdue creation, we do it through the ethical codes and decision-making that are part of an imagined reality. We alone among living beings have that ability. According to the Hebrew Bible, it is what makes us godlike. Our ability to create stories (and its corollary, to be persuaded by them) is important in the biblical framework and is the unique requirement qualifying us to be the gardener in creation.

Probing the meaning of the phrase “in the image of G-d,” reveals that “rule” and “subdue” point to something entirely different from hierarchies, dominance and superiority. Rather the phrase recognizes that human beings have the necessary qualifications to do a particular job in creation. Our unique capabilities for ethical decision-making means we are uniquely responsible.

In case we didn’t get that point in the first three chapters of Genesis, chapter four tells a story of the sad results of an unrestrained hierarchical view of things. By the time we reach the story of Cain and Abel in chapter 4, we are fully enmeshed in hierarchies and objectification, a world in which some are chosen and others are not, living beings have economic value, and violence and aggression rule. We are still in that world. We will continue in it as long as we treat any living being as “less than” another. In the words of Martin Buber, as long as the balance of I-It relationships outweighs I-Thou relationships.

Human life on this planet has an amazing history of insights into the nature of things, a function of our imaginative capability. Using the power of imagination, we perceive through both faith and science the sacred unity of all being — and our particularity of being, each part of creation with its own unique characteristics.

But we humans also often imagine that we are meant to dominate. That our role in creation allows us to destroy. We choose to create hierarchies that rationalize violence toward the planet, toward other species, toward our fellow human beings. We choose to enslave others, deny their natures and roles in creation, and approach them as utilitarian objects here on earth to serve our needs.

The Hebrew Bible shows us what it means to live in a dual reality. We see competing imagined realities in play. And we are regularly reminded of the imperative to choose. Choose what? “Choose life, that you may live.” Not the least of that imperative is that we might make better choices tomorrow, that we might be better gardeners.

Change & Finding Our Story

These last weeks and months of events so significant for our future demonstrate to me that we are in a moment of profound transition to a new story. Unprecedented changes are on the horizon, and we need a framework for ethical decision making in this new environment. Or perhaps we’ll discover the eternal nature of an “old” story, understood in new ways.

I watched a TV series that reminded me of how painful and difficult life’s decisions can be. It also made me think about many things Harari says — and it made me think of the role of religions, ideologies and cultures in shaping the decisions we make and how we make them.

“Humans” is a three-season series available on Amazon Prime. It explores the world Harari imagines when he considers a world in which AI beings evolve to the point where they are potentially capable of replacing humans at the top of the food chain, becoming the dominant beings in creation. As Harari says in Homo Deus, to know what happens when another “species” than our own rises to the top, we need only look at how other species have fared under human domination.

The series is not dystopic. It examines with some nuance and complexity the developing relationship between diverse humans and increasingly diverse “synths,” human-created AI beings who serve humans but along the way develop consciousness. Of course these AI beings are more rational than humans. But in developing consciousness, they not only learn to interpret human emotions better than humans themselves but can themselves feel emotions which, like humans, they manage in diverse ways.

Without sharing spoiler details, the series climaxes when a main character, a champion for synth rights based on her experience of personal involvement with synths, must make a choice between her deep feelings, beliefs and ethical commitments — and her powerful evolutionary instincts. It is not a black-and-white decision. Imagined reality and objective reality struggle. This character struggles with an impossible dilemma. But a choice must be made, and it is agonizing.

So I wonder, what would life be like if — in every moment — we were were fully aware of the central paradox of our existence: living life requires decisions that more often than we like to imagine involve taking life. This basic reality is true even living on carrots. It’s a hard way to live, to start from the premise that all of life is sacred and that it is our sacred task to “rule” over it in a way that allows each part to fulfill a sacred purpose, to sing a unique song of praise.

In fact, it would be almost impossible to make these decisions anew in every moment. So we rely on imagined realities, sets of ethical codes embedded in religions, cultures, constitutions. They become second nature to us so we don’t often have to think about them. Or we imagine our ethical codes to be immutable, fixed for all times and places, which removes from us the burden of making decisions moment by moment.

In fact, this is what the text of the Hebrew Bible proposes: an imagined reality with an ethical code focused on freedom, justice and compassion. Objective reality in the text represents actual human behaviors. Imagined reality represents a potential world that human beings participate in imagining and implementing.

In our time, it feels as though life is changing in ways and at a pace unprecedented in human history. What happens if the earth cannot produce abundantly due to a changing climate? What if there is worldwide starvation far beyond what we see today? If many human beings become “the useless class,” as Harari imagines the possibility? What happens if we develop the capability to extend life indefinitely? Or if “synthetic” beings develop consciousness and threaten our human position at the top of the food chain? Or on a smaller scale, if the United States is no longer in control of its own destiny, we are taken over by a hostile power, external or internal to us? None of these events is completely outside the range of possibility.

But consider the experiences of catastrophic change reported in the Hebrew Bible. Yes, the world was smaller, more local, but it was the entire world to those represented in the text: Abraham and his family leave their home for an unknown world. After settling into a semi-nomadic existence in their new home, a lush and fertile land, they suffer a drought that sends them to Egypt for food where they descend into harsh slavery.

The Israelites are freed, wander through a desert for forty years, establish a kingdom and all the apparatus of state that goes with it, endure a civil war and division of their nation, watch as the northern kingdom is conquered by a powerful Middle Eastern empire, then suffer through that empire’s successor conquering their own southern kingdom.

The Judeans are exiled to alien places and cultures, return in some way and begin a painful and difficult struggle to rebuild. The reestablished nation is enmeshed in bitter sectarianism, and they are unable to cooperate to solve the problems that face them, unable to build the society they are tasked with building. There is a devastating defeat at the hands of the Romans and a second demolition of the nation and culture, brutality, and dispersal once again into alien lands… not easy circumstances to live through individually or as an historical group.

I think this is the beauty, artistry and power of the Hebrew Bible. It presents neither a Pollyanna view of life nor a despairing view. Life unfolds between objective reality and imagined reality. The story singles out the unique characteristic of human beings that might allow them to find solutions and make the kinds of choices that could create a better world, the one way in which humans are godlike. It doesn’t hide the terrible mistaken choices we make along the way or contradictory choices — but it continues to point to our ability to be mindful and to imagine and reimagine our ethics in a world that changes.

Our Sacred Task

Adjusting our imagined reality is never quick or easy. It is painful. It destroys worlds . . . but offers an opportunity to create better worlds. I believe the Hebrew Bible emerged from one of those times in history that required a new imagined reality, a new story, one that could inspire building a better world. I believe we are in one of those times now. What story will we choose? What reality will we create? How will we participate in reimagining received traditions? What will we do with objective realities of our past, things we have done, the consequences of our choices, and how will they fit into our imagined reality going forward?

In the sacred space described in Genesis 1-3, human beings are given a special role, to act as gardeners, nurturing the amazing diversity in the garden of creation — with all the hard choices that imagery suggests. The human adventure in that story was courageous and insightful — and at the same time, foolish, self-absorbed and short-sighted. Yet humanity continued forward in the face of devastation, trying to find a path to make a better world, living between the opposites, we might say: “Life is a particularly intricate natural structure that arises under the right circumstances, between order and chaos.”

What supports opposite and seemingly contraditory themes in the text is a fundamental recognition of interconnection. This is not hierarchy, but a respect for all being. It is a reflection of an intuition Harari ascribes to hunter-gatherers. It is the knowledge that all being, life in all its diversity, sits at the spiritual round table.

We humans are the only beings who can cooperate with many others to put an imagined reality to work. Following the first three chapters of Genesis, the idea of a sacred community striving to create a space, a world in microcosm, of freedom, justice and compassion, becomes the dominant theme in the remaining 926 chapters of the Hebrew Bible. Lots of wrong choices, brutality and devastation along the way, but the effort continues.

Our unique human capability is to create imagined realities, persuade others to share in those realitIes, and cooperate with others to put these imagined realities to work in the world. The Hebrew Bible offers a story that we human beings are the gardeners in creation. Fulfilling that job wasn’t easy for the Israelites — in fact they often failed at it. But they continued to try. They reimagined how to make the world better in the face of catastrophic changes and the consequences of their own bad choices. I still like to imagine that in our own time we can take on the role of gardener. I envision us assisting each part in the whole to fulfill its nature, flourish, and contribute to the well-being of us all. We alone among living beings can fulfill this sacred task that allows G-d’s breath to flow through creation.

A relationship story: biblical myth-making

I love mythology. Like religion, it speaks in the language of “as if.” It is the human story, telling us who we are, where we fit in, our purpose. And our ability to create stories and engage others in them is our unique human capability, the one thing that sets us apart from all other animals. Myth, expressing intuited wisdom, embodies fundamental truths.

Science arrives at truth through a different process and presents the results of the process differently from story. We could say that science and story are like different means of locomotion, all taking us to the same place, but in different ways. Embracing one and ignoring or diminishing the significance of the other risks losing the opportunity for deeper understanding.

Does the relationship story of biblical myth anticipate science?

Today, some mathematicians think the universe may be conscious. Is this what the ancients intuited when they spoke of Elohim (Biblical Hebrew translated “G-d” — or literally “gods”)? Or any of the many other names used biblically and by spiritual seekers over the centuries to refer to an essential unity of all being?

The ancients also intuited that creation is a process that involves organization and creates greater complexity as it continues to unfold. In the biblical story, each stage of G-d’s process of creation involves separating or differentiating (הבדל). G-d separates night from day, dry land from water. As G-d separates and organizes, the world becomes increasingly complex and diverse.

At the same time, the biblical story makes it clear that this unfolding diversity emerges from a single source, G-d.

Then there’s this from Neil deGrasse Tyson: ”Every one of our body’s atoms is traceable to the Big Bang and to the thermonuclear furnaces within high-mass stars that exploded more than five billion years ago…stardust brought to life…” The universe had a beginning. We are made of the same substance as it. We are everything, and everything is us.

Unfolding diversity and complexity from unity sets the stage for a story of relationship.

How the Bible tells a story of unfolding diversity and complexity from unity

But what about the biblical text’s assertion that creation occurred in six days with a seventh day for rest? Science tells us creation “emerged gradually, over billions of years.”

When we approach the text as a story, we recognize that creating in six days and resting on the seventh is a narrative technique. The number seven recurs throughout the biblical text. Stories are structured with seven narrative units, certain words appear seven times in a narrative sequence, holidays and life cycle events like circumcision are presented in seven-plus-one formulations. Seven days serves a narrative purpose. That becomes even more clear when we look at the deeper structure of the first creation story in Genesis 1:1-2:4a:

Day 1: Light, separated light from dark (Gen. 1:3-5)

Day 4: Two great lights, one dominates day, one night (Gen. 1:15-19

Day 2: Expanse, sky, separates waters above from waters below (Gen. 1:6-8)

Day 5: Birds, fish emerge from waters below – fish fill the seas, birds the sky (Gen. 1:20-23)

Day 3: Dry land, earth, emerges when waters are gathered into seas (Gen. 1:9-11)

Day 6: Land animals, including humans (Gen. 1:24-31)

Day 7: G-d rests and blesses the 7th day (Gen. 2:1-4a)

Deep structure of the creation story

There is a lot that could be said here about creation including that it is clearly visualized as a process of organizing, separating, and increasing complexity. But my main point is the careful organization of the narrative itself, the story. Three environments created on Days 1-3. Those environments filled on Days 4-6. Then a day of rest to regenerate and appreciate the results of six days of creative activity.

I’ll leave the extended meaning of this to your own creative imagination. What I’m highlighting is that stories convey truth and meaning differently than science. As story, the biblical text conveys its meaning through literary devices like structure, carefully chosen vocabulary, imagery, allusion, simile. It tells a story of diversity unfolding from and living within unity.

Anthropomorphisms point to relationship

And this brings me to anthropomorphism in the Hebrew Bible. Anthropomorphisms describe non-human entities in human terms. They are like similes in that they compare one thing to another. Unlike similes, anthropomorphisms don’t explicitly announce that they are comparing one thing to another. They simply and directly assign human qualities to non-human entities.

Recognizing human qualities, qualities we ourselves possess, in “the other,” whoever or “whatever” that other may be, is what allows relationship. How can there be a relationship where there is absolutely no commonality? If a being is wholly other from us, or appears to us as wholly other, we cannot relate to that being.

At the same time that we need to see ourselves in the other in order to experience relationship, we need difference, diversity. Otherwise we’re just talking to ourselves. There is no growth opportunity in that. The biblical creation myth points to both in its story.

A relationship story: G-d, non-human animals, the earth itself

The biblical story tells us that G-d is different from G-d’s creation, that G-d is beyond our comprehension. Paradoxically, it tells us we can have a relationship with G-d. One of the ways this story affirms the latter is through anthropomorphisms that imagine qualities G-d shares with created beings.

The biblical story also uses anthropomorphisms to tell us we are like our fellow creatures in significant ways. A snake that stands upright, strategizes, manipulates and speaks is so much more than “mere folklore,” to be dismissed. So is a talking donkey that “sees” better than a seer and has a sense of justice. These are stories bearing important truths, the truth of relationship.

Finally, the biblical story speaks of the land with anthropomorphisms. Acting as God’s agent, the land “vomits” out those who live on it if they fail to care for the vulnerable in society. It can be called to witness in a trial. It nurtures and it punishes. In this way, we are drawn into a relationship not only to G-d, not only to our fellow creatures, but to the land and air and water that offers a habitat for us all. (Gen. 1:1-2:4a).

The simple but amazing idea is that the glorious diversity of an unfolding universe of being emerges from, lives within, and participates in a unity. Whether we “believe” or “disbelieve” it doesn’t change anything except our own way of being in the world. It simply is.

Recognizing our commonality, our unity in diversity

We all know that G-d doesn’t literally and physically walk in the garden in the heat of the day. We also know that snakes don’t speak in Hebrew or any other human language and that land doesn’t “vomit” out those who live on it if they fail to care for the vulnerable in society. It doesn’t act as a witness in a trial. The biblical “author,” whether it was G-d or a human being or a group of human beings knew those things as well as we do.

But the Hebrew Bible brings us an eternal truth, one that science now tells us through its own process: there is an essential unity behind, before, and within the diversity of creation. This unity IS creation. Our beautiful diversity combined with our unity of being, our commonality, is what allows relationship, the kind of relationship that happens when you recognize some part of yourself in the other.

Anthropomorphism is a shorthand way of recognizing commonality in the midst of the vast diversity of being. It is the combination of diversity and shared traits that makes a space in which human beings can be in a relationship with G-d, with nonhuman animals, with the heavens and the earth, with everything that is. Even in this profusion of diversity, there is the potential to glimpse ourselves in the other.

Imagine…

What a profound idea that is! Where might we be in our history on this planet if the primary objective of our lives, our reason for being, were to cultivate an awareness of our relationship to everything that is, to nurture it, and to serve those relationships lovingly?

The Animals’ Story in the Torah

In The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible, Charles Eisenstein coins the word, “Interbeing,” a knowledge “that my being partakes of your being and that of all beings. This goes beyond interdependency—our very existence is relational . . . that purpose, consciousness, and intelligence are innate properties of matter and the universe.”

This story of Interbeing is one I once knew — but on January 20, 2017, I woke up depressed, and I wondered how the world, how I, had strayed so far from that knowledge of Interbeing. Instinctively I turned toward projects I hoped might reawaken my consciousness of myself in that story. I hoped to expand the circle of my own often limited awareness and compassion.

I reinvested in my exploration of veganism, creating beautiful food from what the earth gives us so abundantly. I went to work on a farm, spending hours with my hands in the earth helping to grow the food I prepared at home. And I started another journey through the Torah with a different lens, relationships. I called this project “Torah Ecology.”

After a time, I focused more sharply on a particular set of relationships, that between human and nonhuman animals. The story I found in the Torah convinced me that its foundation story is the story that Charles Eisenstein describes in one simple but rich word, Interbeing.

Today, 2500 years after the time many scholars believe the text was redacted into the form we have it today, science tells us the same story.

These additional readings helped me in my journey: Charles Eisenstein’s, The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know Is Possible, Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind and Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, Nathan Lents’ Not So Different: Finding Human Nature in Animals, Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate―Discoveries from A Secret World and The Inner Life of Animals: Love, Grief, and Compassion―Surprising Observations of a Hidden World, Barbara J. King’s Personalities on Our Plate: The Lives and Minds of Animals We Eat, Franz van de Waal’s Mama’s Last Hug: Animal Emotions and What They Tell Us about Ourselves, and from Sierra Club’s March/April 2019 issue, this feature story: “Does A Bear Think In the Woods?” There are other books I look forward to reading, including more from Frans van de Waal and several from Mark Bekoff.

Like the Torah, these books point directly or indirectly to the fact that nonhuman animals have consciousness, intelligence, a sense of fairness and justice and empathy. They plan and cooperate. They also experience fear and jealousy and act aggressively toward those who threaten them. Human beings are firmly in the animal kingdom. As Yuval Noah Harari points out, we had a mediocre position in the food chain until a time in human evolution when we didn’t.

These facts raise obvious questions. Is there a moral argument for taking the life of other living beings because they differ from us? Do human beings possess unique characteristics that allow them to claim superiority over other animals, providing a rationale for sacrificing them in payment for our own sins? Surely the Torah doesn’t give us the right to commercialize life as we have today, breeding animals by the billions each year only to kill and eat them, destroying the planet as we do it. Surely the Torah points to an awareness that these are our fellow creatures, other beings who share our beautiful, living planet with us.

In any discussion of meat eating, many will quickly point to repeated references throughout the biblical text that put forward the sanctity and supreme value of human life. Or will point to the explicit permission to eat other living beings in Gen. 9:3:

כָּל־רֶ֙מֶשׂ֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר הוּא־חַ֔י לָכֶ֥ם יִהְיֶ֖ה לְאָכְלָ֑ה כְּיֶ֣רֶק עֵ֔שֶׂב נָתַ֥תִּי לָכֶ֖ם אֶת־כֹּֽל׃

Every creature that lives shall be yours to eat; as with the green grasses, I give you all these.

And what do we do with Leviticus, a book with animal sacrifice at its heart? My project stalled for a time here as I studied it through the lens of the human-nonhuman animal relationship. How can I say the fundamental Torah story is that of Interbeing when the violence of one being toward another is at its literal center? (Leviticus is the central book and the Yom Kippur sacrifice is at its center). How does animal sacrifice connect with Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel’s “radical amazement” or Martin Buber’s idea of “I-Thou” relationships? As I worked through my project, I had to confront those questions. In what follows, I will incorporate my thoughts with regard to them.