All in the Family: Transactions

וְהָ֣אָדָ֔ם יָדַ֖ע אֶת־חַוָּ֣ה אִשְׁתּ֑וֹ וַתַּ֙הַר֙ וַתֵּ֣לֶד אֶת־קַ֔יִן וַתֹּ֕אמֶר קָנִ֥יתִי אִ֖ישׁ אֶת־יְהוָֽה׃

Now the man knew his wife Eve, and she conceived and bore Cain, saying, “I have gained a male child with the help of the LORD.” (Gen. 4:1)

And so begins the tragedy of Cain, born to a mother who views his birth and her relationship to this son through a transactional lens. While קַ֔יִן (Cain) doesn’t derive from קָנִ֥יתִי (gained/acquired/purchased), the alliteration (ka-yin, kaniti) links his name to Eve’s description of his birth.

In contrast, we read of the birth of Abel simply:

וַתֹּ֣סֶף לָלֶ֔דֶת אֶת־אָחִ֖יו אֶת־הָ֑בֶל וַֽיְהִי־הֶ֙בֶל֙ רֹ֣עֵה צֹ֔אן וְקַ֕יִן הָיָ֖ה עֹבֵ֥ד אֲדָמָֽה׃

She then bore his brother Abel. Abel became a keeper of sheep, and Cain became a tiller of the soil. (Gen. 4:2)

Abel’s very name (הָ֑בֶל – Havel), meaning vapor or breath, alludes to his vulnerability, the vulnerability we usually associate with an infant. At the same time, the word can mean “worthless,” as in Ecclesiastes 1:2: הַכֹּל הֶבֶל (All is fruitless/worthless), contrasting with Cain’s worth, alluded to in Eve’s reference to “gain.”

Two infants, one referred to by his mother as gain or enrichment, the other as vulnerable and possibly of no value. And a father who is not in the picture after impregnating his wife. What a sad portrayal of the first human family. What could possibly go wrong?

The names of the infants and their mother’s attitude toward them also hint at their future. As Cain’s mother’s relationship with him is transactional, so is Cain’s relationship with God. How could it be otherwise? Children reflect the relationships they have with their parents in their own relationships as they grow. And Abel is but a breath, a brief and vulnerable life.

וַֽיְהִ֖י מִקֵּ֣ץ יָמִ֑ים וַיָּבֵ֨א קַ֜יִן מִפְּרִ֧י הָֽאֲדָמָ֛ה מִנְחָ֖ה לַֽיהוָֽה׃

In the course of time, Cain brought an offering to the LORD from the fruit of the soil;

וְהֶ֨בֶל הֵבִ֥יא גַם־ה֛וּא מִבְּכֹר֥וֹת צֹאנ֖וֹ וּמֵֽחֶלְבֵהֶ֑ן וַיִּ֣שַׁע יְהוָ֔ה אֶל־הֶ֖בֶל וְאֶל־מִנְחָתֽוֹ׃

and Abel, for his part, brought the choicest of the firstlings of his flock. The LORD paid heed to Abel and his offering,

וְאֶל־קַ֥יִן וְאֶל־מִנְחָת֖וֹ לֹ֣א שָׁעָ֑ה וַיִּ֤חַר לְקַ֙יִן֙ מְאֹ֔ד וַֽיִּפְּל֖וּ פָּנָֽיו׃

but to Cain and his offering He paid no heed. Cain was much distressed and his face fell.

וַיֹּ֥אמֶר יְהוָ֖ה אֶל־קָ֑יִן לָ֚מָּה חָ֣רָה לָ֔ךְ וְלָ֖מָּה נָפְל֥וּ פָנֶֽיךָ׃

And the LORD said to Cain, “Why are you distressed, And why is your face fallen?”

הֲל֤וֹא אִם־תֵּיטִיב֙ שְׂאֵ֔ת וְאִם֙ לֹ֣א תֵיטִ֔יב לַפֶּ֖תַח חַטָּ֣את רֹבֵ֑ץ וְאֵלֶ֙יךָ֙ תְּשׁ֣וּקָת֔וֹ וְאַתָּ֖ה תִּמְשָׁל־בּֽוֹ׃

“Surely, if you do right, There is uplift. But if you do not do right Sin couches at the door; Its urge is toward you, Yet you can be its master.” (Gen. 4: 3-7)

There is no suggestion in this story that Cain experiences loving intimacy, not with his parents, not with God. Cain brings an offering “in the course of time,” eventually, without any sense of urgency. The offering isn’t remarkable. It’s not singled out as the best of what he has to offer or as first fruits. There is no sacrifice involved.

Cain’s offering, like his life in general, is transactional in nature. There seems to be an assumption in the text that an offering is due. Cain brings the offering but with a minimum expenditure of energy and resources.

In contrast, Abel brings the choicest (וּמֵֽחֶלְבֵהֶ֑ן) of the firstlings of his flock. He brings to God the fat of the lambs, his most precious lambs, the firstlings. It is easy to imagine that for a shepherd, these firstlings have more than economic value. Giving them up is a sacrifice, economically and emotionally painful.

Before heaping all the responsibility for a transactional worldview on Cain, though, or on Eve, his mother . . . or even on humanity . . . I wonder. Is God, too, implicated in this view of relationship?

While the text doesn’t explicitly state that God requires sacrifice in exchange for giving life and a beautiful and abundant world in which to live it, where else would Cain and his brother, Abel, have gotten the idea that a sacrifice was required? And the text does tell us that God appreciates Abel’s sacrifice more than Cain’s. In this way, the story may suggest that God, too, has a transactional view of relationships. There is an implied economy of being in this universe.

This transactional view turns out to be the basis of animal sacrifice, as we will see in later chapters.

The Root of Transaction: Desire

The worldview presented in the Cain and Abel story is very different from that of Genesis 1-3, but the seeds of the latter are in the former. Compare these two verses, one from the Creation Story and the other from the current story of Cain and Abel:

וְאֶל־אִישֵׁךְ֙ תְּשׁ֣וּקָתֵ֔ךְ וְה֖וּא יִמְשָׁל־בָּֽךְ׃

“Yet your urge shall be for your husband, And he shall rule over you.” (Gen. 3:16)

חַטָּ֣את רֹבֵ֑ץ וְאֵלֶ֙יךָ֙ תְּשׁ֣וּקָת֔וֹ וְאַתָּ֖ה תִּמְשָׁל־בּֽוֹ׃

“Sin couches at the door; Its urge is toward you, Yet you can be its master.” (Gen. 4:7)

The first verse, Gen. 3:16 is in the context of God telling Adam and Eve how things will be going forward. In a word with sexual overtones, teshukatech, God declares that a woman’s longing and desire (urge) will be toward her husband — and that he will rule (yimshol,יִמְשָׁל) over her.

In the current story of Cain and Abel, Gen. 4:7, God warns Cain of sin, personified and “couching” at the door. The longing and desire (teshukato, urge) of this sin, a seductive, sinister, lurking external entity, is toward Cain — but as God instructs, Cain can rule (timshol, תִּמְשָׁל) over it if he chooses.

Why is this juxtaposition of detail important? Because both Adam and Cain, representing humanity, are set to rule over creation, over all creatures both seen and unseen, but both find it exceedingly difficult to do. They can scarcely rule over themselves. And as they fail in their task, they blame what appears to be external to them, Adam blaming Eve and Cain his brother, Abel.

Neither recognizes their own responsibility in the choices that result in sin. Both bring into existence the sin lurking seductively outside the door waiting for the right moment to spring into action through human agency. Sin, like the love and abundance imagined in Gen. 1-3, is mere potential until human choices make it reality. Then it becomes part of a person, desire rules human nature, and transactions prevail over gifting, subverting the intended order of creation.

The Ground Beneath Our Feet

Even the ground is called to task for swallowing the blood of Cain’s dead brother, Abel, as well as Cain for spilling that blood onto the ground:

וַיֹּ֖אמֶר מֶ֣ה עָשִׂ֑יתָ ק֚וֹל דְּמֵ֣י אָחִ֔יךָ צֹעֲקִ֥ים אֵלַ֖י מִן־הָֽאֲדָמָֽה׃

Then He said, “What have you done? Hark, your brother’s blood cries out to Me from the ground!

וְעַתָּ֖ה אָר֣וּר אָ֑תָּה מִן־הָֽאֲדָמָה֙ אֲשֶׁ֣ר פָּצְתָ֣ה אֶת־פִּ֔יהָ לָקַ֛חַת אֶת־דְּמֵ֥י אָחִ֖יךָ מִיָּדֶֽךָ׃

Therefore, you shall be more cursed than the ground, which opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood from your hand.

כִּ֤י תַֽעֲבֹד֙ אֶת־הָ֣אֲדָמָ֔ה לֹֽא־תֹסֵ֥ף תֵּת־כֹּחָ֖הּ לָ֑ךְ נָ֥ע וָנָ֖ד תִּֽהְיֶ֥ה בָאָֽרֶץ׃

If you till the soil, it shall no longer yield its strength to you. You shall become a ceaseless wanderer on earth.” (Gen. 4:10-12)

The ground, already cursed in Gen. 17, withholding its abundance from Adam, will now withhold its abundance from Cain, Adam’s first son. And the humans, living but alienated from the connectedness of all being, increase the distance between themselves and a living but unyielding earth. Cain, condemned to wander the earth, leaves the presence of the Lord, settles in another land with his wife, fathers a son, Enoch, and founds a city in his son’s name:

וַיֵּ֥צֵא קַ֖יִן מִלִּפְנֵ֣י יְהוָ֑ה וַיֵּ֥שֶׁב בְּאֶֽרֶץ־נ֖וֹד קִדְמַת־עֵֽדֶן׃

Cain left the presence of the LORD and settled in the land of Nod, east of Eden.

וַיֵּ֤דַע קַ֙יִן֙ אֶת־אִשְׁתּ֔וֹ וַתַּ֖הַר וַתֵּ֣לֶד אֶת־חֲנ֑וֹךְ וַֽיְהִי֙ בֹּ֣נֶה עִ֔יר וַיִּקְרָא֙ שֵׁ֣ם הָעִ֔יר כְּשֵׁ֖ם בְּנ֥וֹ חֲנֽוֹךְ׃

Cain knew his wife, and she conceived and bore Enoch. And he then founded a city, and named the city after his son Enoch. (Gen. 4:16-17)

From Abundance to Scarcity

So we are no longer in the world of the first three chapters of Genesis, a world filled with joyful energy, overflowing abundance and harmony. A world in which all beings share the spiritual round table. In the Cain and Abel story, we find ourselves in a world of separation and scarcity, a transactional world that assigns value to living beings, a world of competition, envy, desire, violence and animal sacrifice.

The story of Cain and Abel is one of the increasing alienation of Cain from his parents, from his own brother, from God, from humanity, and finally from the earth itself. What is the source of Cain’s anger? What causes the tragedy and isolation of his life?

The literary details of the story suggest that tragedy begins with Cain’s transactional relationships from the day he is born. What an odd statement Eve makes about his birth, that she “acquired” a child as though he is an item she purchased at the market. There is a profound emptiness associated with that word in this context. We can only imagine the additional pain Cain must experience as he learns that God notices Cain’s brother, Abel, and favors Abel’s offering over Cain’s own.

Cain’s response to God taking note of Abel’s offering is another story element that builds on the transactional theme. Cain brings an offering — and expects a particular return for it, turning the offering into a transaction.

In contrast, the first humans, Adam and Eve, are part of an abundant world they share with non-human animals and with God. They are gardeners, caring for the world God gifts to them. “In the beginning,” they live in harmony with their world.

Did the characters “evolve” through the story? The text suggests, perhaps not. At the end of Gen. 4, Adam and Eve once again have a child, a third son:

וַיֵּ֨דַע אָדָ֥ם עוֹד֙ אֶת־אִשְׁתּ֔וֹ וַתֵּ֣לֶד בֵּ֔ן וַתִּקְרָ֥א אֶת־שְׁמ֖וֹ שֵׁ֑ת כִּ֣י שָֽׁת־לִ֤י אֱלֹהִים֙ זֶ֣רַע אַחֵ֔ר תַּ֣חַת הֶ֔בֶל כִּ֥י הֲרָג֖וֹ קָֽיִן׃

Adam knew his wife again, and she bore a son and named him Seth, meaning, “God has provided me with another offspring in place of Abel,” for Cain had killed him. (Gen. 4:1)A son is gone — a replacement provided. Like Eve’s comment about Cain, that she “acquired” a son, her comment about Seth, that he replaces Abel, leaves us with a feeling of emptiness. Eve’s unemotional evaluation of her situation is surprising. It’s hard to imagine life improving for this family as they move into their future.

The story of Seth’s birth continues in Gen. 5:1-3. We return to a theme of Gen. 1, a hierarchical worldview in which Adam is to his third son, Seth, as God is to Adam:

זֶ֣ה סֵ֔פֶר תּוֹלְדֹ֖ת אָדָ֑ם בְּי֗וֹם בְּרֹ֤א אֱלֹהִים֙ אָדָ֔ם בִּדְמ֥וּת אֱלֹהִ֖ים עָשָׂ֥ה אֹתֽוֹ׃This is the record of Adam’s line.—When God created man, He made him in the likeness of God;

זָכָ֥ר וּנְקֵבָ֖ה בְּרָאָ֑ם וַיְבָ֣רֶךְ אֹתָ֗ם וַיִּקְרָ֤א אֶת־שְׁמָם֙ אָדָ֔ם בְּי֖וֹם הִבָּֽרְאָֽם

male and female He created them. And when they were created, He blessed them and called them (hu)man… (Gen. 5:1,2)

וַֽיְחִ֣י אָדָ֗ם שְׁלֹשִׁ֤ים וּמְאַת֙ שָׁנָ֔ה וַיּ֥וֹלֶד בִּדְמוּת֖וֹ כְּצַלְמ֑וֹ וַיִּקְרָ֥א אֶת־שְׁמ֖וֹ שֵֽׁת׃

When Adam had lived 130 years, he begot a son in his likeness after his image, and he named him Seth.

God creates and humans give birth . . . And as the humans are in the image and “likeness” of God, so Seth is in his father’s “likeness” and “image.” Do these echoes of the first chapter of Genesis suggest a repetition of the experience of the first family . . . Or are they more hopeful, foreshadowing a new creation, coming in the events of the Flood and following?We leave the story skeptical of a future built on either a transactional or a hierarchical foundation . . . But perhaps also with some hope that life goes on, and a fresh start may go better.

Postscript on the Cain and Abel story

In Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, Prof. Yuval Noah Harari describes the evolution of religions from animism to polytheism to monotheism. Of animism, he says, “When animism was the dominant belief system, human norms and values had to take into consideration the outlook and interests of a multitude of other beings, such as animals, plants, fairies and ghosts…Hunter-gatherers picked and pursued wild plants and animals, which could be seen as equal in status to Homo sapiens. The fact that man hunted sheep did not make sheep inferior to man, just as the fact that tigers hunted man did not make man inferior to tigers. Beings communicated with one another directly and negotiated the rules governing their shared habitat.”

Conversely, “farmers owned and manipulated plants and animals, and could hardly degrade themselves by negotiating with their possessions. Hence the first religious effect of the Agricultural Revolution was to turn plants and animals from equal members of a spiritual round table into property.”

Perhaps these different worldviews are one way to think about the difference between Gen. 1-3 and Gen. 4-7. What if the first chapters of Genesis represent a hunter-gatherer worldview while the story of Cain and Abel points to a worldview more closely associated with an agricultural setting? If the agricultural revolution signifies a transition from a world in which “beings communicate with one another directly and negotiate the rules governing their shared habitat” to a transactional world of ownership and wealth, it also signifies a transition from a mindset of abundance and gifting to scarcity, greed and jealousy. Possessions necessitate guarding, and unequal distribution generates desire and envy.

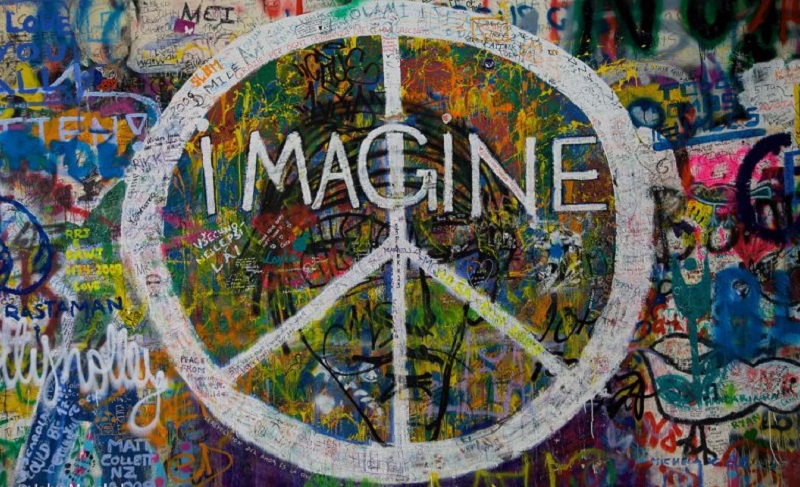

Yet as Charles Eisenstein points out in Sacred Economics: Money, Gift and Society in the Age of Transition, we are not fated to live in one world or the other. Our world is what we make it, the story we create and in which we choose to stand. Harari, too, tells us that the human ability to create fictions, to imagine, and then to persuade many others to believe our fictions, is a unique characteristic of Sapiens. It is that unique ability that allowed humans to “rule over” creation.

Reimagining Creation, Our Human Purpose

At any moment, we can place ourselves back in the Garden, that world in which all beings communicate “with one another directly” and negotiate “the rules governing” our “shared habitat.” We can share the spiritual round table. We can create a world of abundance, freeing ourselves to share and live harmoniously with each other, other beings and with the earth itself.

Or our existence can be transactional, measured, even self-serving. We can view the world as a place of scarcity, guarding our possessions and wealth jealously in our state of alienation and viewing others in a utilitarian way (Martin Buber’s “I-It” way of relating) or with suspicion and fear. It all depends on the power of our imagination and the way we choose to use it.

And this brings me to the message of faith in the amazing ancient text which is the Torah. The times that serve as the backdrop to the biblical text were not free from scarcity and bloodshed. I imagine there was as much cause to feel overwhelmed by fear, suspicion, anger, grief and despair then as now. The text describes many of those events, wars, famine, disease, loss of home and family.

The Torah doesn’t deny or neglect those realities. It doesn’t whitewash the nature of human beings or of other living beings and doesn’t deny that the earth itself can be intransigent. There is no horror in our world today that doesn’t find its echoes in those times. Yet the vision that drives this text, the story that it insists on telling in the face of tragic circumstances, is a story in which there is meaning, justice, beauty, harmony and great abundance for all creatures.

There is, after all, something eternal in the Torah story even in a secular age. It is a story about the reality of our existential condition but also about the power of imagination to create worlds. What world do we want to create? A transactional world of scarcity, alienation and fratricide or a world of abundance and harmony, where we share the spiritual round table with all other living beings? The world we live in is the world we imagine into reality. The Torah shows us both and urges us to “Choose life…” (Deut. 30:19)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Addendum: January 10, 2021 – I think this story also points to the twin themes of ruthless self-preservation and altruism / reciprocity. According to evolutionary science, acting from self-interest preserves and enhances the life of the individual, but acting on the basis of altruism and reciprocity preserves the life of the group or species.

I can see these two characters, Cain and Abel, as archetypes of these twin themes. This kind of pairing is a frequently used biblical technique that points to wholeness. Cain’s self-interested, transactional orientation leads to his personal survival. Abel, who dies in the short term, contributes to long term human preservation in the symbolism of the story by serving and gaining merit with the God who created humanity. But the choice the story points to isn’t one or the other — it’s both, held in balance within one individual or one social network.