I began my current journey in biblical studies six years ago on a walk with my violence-averse husband. A dead and partially mutilated rabbit ended our stroll around the neighborhood with his exclamation of dismay. I asked why “these kinds of things,” which include National Geographic specials that involve one animal hunting and killing another, disturb him so much, glibly announcing, “It’s just the plan of nature.” He responded, “It’s a stupid plan.”

My husband’s comment surprised me, but then I started thinking. In a universe of infinite possibilities, why couldn’t things be different? What if living life didn’t require taking life? Going a step further, what if there were, in fact, no death?

I’m not the first to wonder, what if? That thought long ago occurred to others. This is the world imagined into being in the first three chapters of Genesis. All animals, human and non-human, were vegan, and there was no death.

Recently on another walk as I was spinning out my newest thought process for my patient husband, I reminded him that this all began from his comment six years ago. This time he added, ”Yes, I wonder why all animals couldn’t have just grazed?” Which caused me to speculate that then there would have been no population control. P’ru u’r’vu (be fruitful and multiply), a command given to all living beings, would have become a planetary death sentence.

So Genesis 1-3 imagines the beautiful world, a world of unrestrained creativity, abundance and no death, a world that crashes into another story of human drives in a world of limited resources and death, the remaining 184 chapters of Torah.

This collision should cause us to sit up and take notice. As Joseph Campbell once said, “Life lives on life. This is the sense of the symbol of the Ouroboros, the serpent biting its tail. Everything that lives lives on the death of something else. Your own body will be food for something else. Anyone who denies this, anyone who holds back, is out of order. Death is an act of giving.”

Isn’t this Economy of Being the problem that Thanos, in the Marvel Cinematic Universe (The Avengers and Guardians of the Galaxy), set out to solve? Too much stress on limited resources? And like the God of the Bible, Thanos sets in motion a plan to randomly reduce the population. Unlike God’s plan in the Bible, Thanos’ plan applies only to humanity (or at least the story deals only with humanity) — and was applied directly, not through the workings of nature. But the initiating challenge and its resolution were effectively the same. “Be fruitful and multiply“ requires a counterbalancing mechanism.

In the Marvel Comics universe, Thanos was not a completely unsympathetic character. He suffered when he saw the results among humans of unrestrained evolutionary success. He thought he had a plan to “fix” that. Randomly eliminating half the population would allow the other half to live comfortably, without suffering. A painful job, but someone had to do it.

Of course, it was satisfying when Thanos was finally vanquished, and those who had been eliminated were returned to life — but this ending begged the question: what provides the counterbalance to the creative urge, the urge of a species to expand to the point of wiping out other planetary resources? Where is the Economy of Being?

The “good guys,” those who vanquished Thanos and brought back the missing half of humanity, didn’t answer that question. So who were the good guys? Thanos, who took responsibility and acted even if we don’t like the action? Or the Guardians, who did something we like better but didn’t address the problem?

Both stories, one from the Marvel Cinematic Universe and one from the Torah, address the same issue. Living beings drive toward their own evolutionary success. But unrestrained success is ultimately destructive. Both stories recognize the need for a counterbalancing force, a limiting factor, and in both stories that limiting factor involves death. Both stories have an issue of justice in their background as one randomizes death (Marvel), and the other universalizes it (Torah). In neither case do living beings live or die based on merit.

Only one of the stories places the responsibility for the problem and its solution on living beings themselves: the Torah story. Human beings and a fellow creature, a serpent, interact destructively in a way that brings death to the world. Forced to recognize their responsibility, they are also required to participate in a solution. Consider the power of this story that over the millennia has insisted on engaging living beings, primarily humans, in maintaining an Economy of Being. We have often fulfilled that responsibility poorly if at all.

The Torah story with its nuance leaves us at the heart of the dilemma. It doesn’t give us a single answer. There is more than one “creation” story, more than one attempt to create a world without violence and suffering. Finally multiple voices and stories are woven together, acting as a vehicle of acculturation. A subset of humanity, the Israelites, receives a body of laws, hopefully producing better outcomes for all life on the planet than when human animals simply follow their unrestrained evolutionary urges. And the story continues.

“Us-Themism”

I imagine some of us would call the creative urge, the drive to “be fruitful and multiply” in all its variations, a ”good” impulse — and those things that limit that drive, including a predatory impulse, “bad.” And yet, in evolutionary terms, both are necessary and therefore, objectively speaking, neither good nor bad.

In Jewish tradition, these drives and impulses are recognized as yetzer ha tov and yetzer ha-ra, the good inclination and the evil inclination. The good inclination isn’t good in and of itself, nor is the evil inclination evil. We might think of the good inclination as an altruistic impulse which, when taken to an extreme, results in the death of an organism. Similarly the evil inclination is responsible for creating, building, developing, but in the extreme, results in greed, predation, suffering and even death to others.

This makes things more complicated for us. How do we know when to give and when to take, when to cooperate and when to compete? When to focus on “us” and when to be wary of “them?” The answers are rarely clear-cut, and those stories sustain us best that are nuanced enough to replicate the complexity of our lives.

Torah stories like the Flood story teach that since these drives are in the makeup of the human animal, our goal should not be to repress or sublimate these urges, to “cure” ourselves of them, but to keep them in balance. In this way, Jewish law is also a story, a means to acculturate us to become the best human beings we can be.

Like many in my generation, I imagine, I grew up disdaining the tribal mentality, an Us/Them worldview. After all, we are all human. And beyond that, we are all creatures animated by the breath of God — or at least are in the same boat on this planet and will either float together or die together.

But now we know, as Jewish traditions intuited, this Us/Them mentality that expresses itself so consistently throughout history is a necessary evolutionary trait, one of those variations on the drive that limits the suffering and evil that would result from unrestrained p’ru u’r’vu, fruitfulness and multiplication.

So according to science, Us/Them-ing is an evolutionary trait with a specific purpose, perhaps even multiple purposes. One that stands out is that when resources are limited, an “Us” group is more likely to succeed when “They” are minimized, utilized, or eliminated. Returning a nonhuman animal to the wild that has lived with humans makes clear the danger in modifying the instinct to be wary of “Them.” So we need to respect that instinct in ourselves and other living beings.

But are we doomed to forever look with suspicion on the Other or to minimize their being in relation to our own? Even to commit violence against them? The world’s religions have all said “no.” And here is the role of the powerful story, the story that acculturates us, shapes a worldview, that drives us with greater force than our evolutionary instincts.

It is our stories that give us the capability of modifying our relationships with others. Yuval Noah Harari tells us that the distinctive trait of Sapiens that pushed us to the top of the food chain is our ability to create fictions and persuade others to believe them. This ability, in turn, allows us to cooperate flexibly in large groups. Harari names as fictions religions, corporations, banks and nations among others — basically anything that shapes our world. I like to call these fictions stories. Our stories are not only our downfall but our potential salvation.

Finding Our Story

Just when we need a good story, we live in times when the stories we knew are crumbling, are no longer effective. This applies to our religious stories as well as our cultural and national stories. Millennials are leaving institutional religious life in droves. Dictatorships are replacing democracies. The institutions and value systems we shared and loved, that grew out of our stories, are shredded before us.

Discovering meaning in old stories or finding and creating new stories, though, is even more difficult when we disdain everything that isn’t “fact” or “science.” I have some sympathy with Kellyanne Conway’s comment about alternate facts. I think what she might have meant, or at least should have said, was “alternate stories“ — because it is our stories that give meaning to facts. Myth gives meaning to history, to human experience.

Here’s how one writer says it: “It’s all a question of story. We are in trouble just now because we do not have a good story. We are in between stories. The old story, the account of how the world came to be and how we fit into it is no longer effective. Yet we have not learned the new story. Our traditional story of the universe sustained us for a long period of time. It shaped our emotional attitudes, provided us with life purposes, and energized action. It consecrated suffering and integrated knowledge. We awoke in the morning and knew where we were. We could answer the questions of our children. We could identify crime, punish transgressors. Everything was taken care of because the story was there. It did not necessarily make people good, nor did it take away the pains and stupidities of life or make for unfailing warmth in human association. It did provide a context in which life could function in a meaningful manner.” ~ The Dream of the Earth by Thomas Berry (Sierra Club Books, 1988, p. 123 )

When we minimize the power of our stories, when we fail to find and choose a story in which to stand, we leave the field open to others who appreciate the power of stories and use them to their advantage, planting their stories, which then have a chance to put down roots and flourish. We leave the field to those whose stories rationalize building massive vertical chicken farms or to industrial animal agriculture operations, to those whose stories center around financial success as the greatest value, to those whose stories feature victimization and blame, to Nazis and white supremacists, to ISIS.

If stories give facts their meaning, if stories are the one thing more powerful than evolutionary drives like our natural instinct to be wary of “the other,” even to devalue, minimize, commercialize, or prey on the other, then presenting unadorned facts to a person driven by a powerful story with which we disagree is unlikely to have any effect at all. It’s like speaking in completely different languages.

In When Elephants Weep: The Emotional Lives of Animals, authors Jeffrey Masson and Susan McCarthy point out that until very recently, scientists have refused to speak in terms of animal emotions for fear of being accused of anthropomorphizing and consequently discredited. In this way, a story was generated that supports a giant and brutal animal agriculture industry and contradicts what is obvious to any casual observer.

The story that animals don’t experience emotions and intelligence like humans, also contradicts what we once knew before we placed ourselves so solidly in the story of science, a one-sided science that minimizes the value of, or even rejects, the information brought to us through the humanities.

A course from Yale University, offered through Coursera, Journey of the Universe, says it this way: “The Journey course . . . is based on a new integration that is emerging from the dialogue of the sciences and humanities. Journey tells the story of evolution as an epic narrative, rather than as a series of facts separated by scientific disciplines.”

A parallel process of reshaping the scientific narrative is happening with regard to animals and animal studies. When Elephants Weep is just one of a large number of studies and books coming out in recent years. These scientists and observers are looking more closely at what we share with our fellow living beings on the planet. They are presenting an alternative to the story of minimization.

This new scientific story and this new narrative of the human-nonhuman animal relationship parallels the Torah story, which describes both human and nonhuman animals as flesh animated by the breath of God.

Like their human animal counterparts, nonhuman animals are intelligent, can strategize, have feelings and are held morally accountable. Human animals, like their nonhuman animal counterparts, are driven by evolutionary instincts including cooperation — but also “Us-Themism.”

It occurs to me that humans‘ unique characteristic, that which differentiates us from nonhuman animals, is our ability, as Harari points out, to create stories. Potentially those stories could help us overcome or at least redirect our tendency to violence. Not always, perhaps not even often, but it might. This is God’s theory after the Flood when God permits meat-eating.

Our stories shape our lives and give them meaning. The Torah provides a story for those who would eat our fellow creatures . . . but also a story for those who would not. It provides a story in which animal sacrifice is at the center of an Economy of Being — and Jewish history and experience provides another that replaces sacrifice with prayer.

Our society provides a story for those who breed and fatten billions of living beings each year for slaughter. We are in a process of rediscovering the story of our interconnection, even interbeing, and conscious choice. It is a long, slow and difficult journey of rediscovery, but it is imperative. To save ourselves, we need to find and choose and share that story that is stronger than our evolutionary drives.

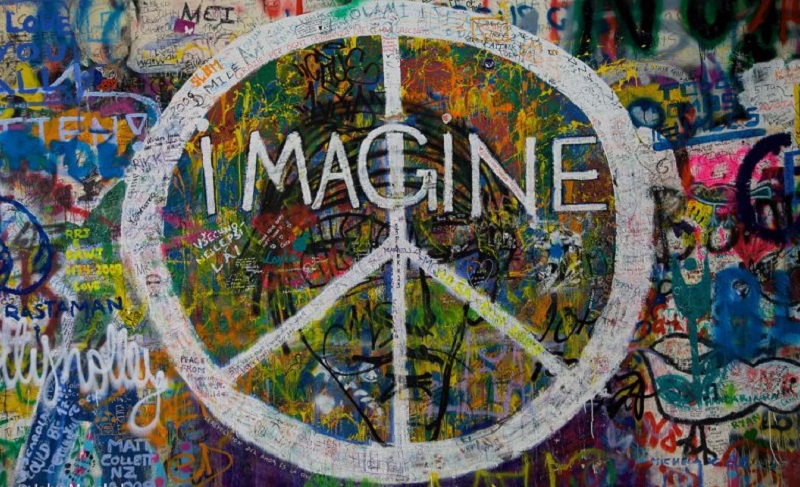

“Imagine Peace” by johnmaschak is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0