Part I: Speciesism

I’ve spent most of the last year focused on the broader Torah story, its worldview as I understand it through my study. This worldview is expressed primarily through a human lens and involves the relationship of human beings with Transcendence, Creation, and Other Life, which further divides into Other Living Creatures and Other Human Beings. Recently I have come to focus more narrowly on the relationship between human beings and their fellow creatures. Although the move was intuitive, it was generated by my growing certainty that our complex relationship with our fellow creatures signifies our core moral problem: speciesism.

Speciesism requires two fundamental mental and spiritual dispositions: 1) the way in which we, personally, see the world is reality and is true, and 2) “the other,” any living being who is different from us, is inferior to us. In reality, neither disposition has any evidence to support it.

Our attitude toward other living creatures inspires — or infects — our attitude toward other human beings. Our vocabulary shows how we made that link subconsciously over centuries. Any group of humans we want to degrade we refer to as animals.

The act of minimizing “the other” occurs first with animals. As we subconsciously learned not to question the assumption that we are superior to the animals, it became easier to thoughtlessly apply that same assumption to our fellow human beings. Further if factory farms have taught us nothing, they have taught us that when things happen out of sight, it is much easier to escape any sense of moral responsibility that results from our unchallenged assumptions.

So for me, one of the practices I have tried to strengthen in myself as I study is to discover and set aside any assumptions I hold — about the Torah, about animals, about other people — and to set aside any conscious or unconscious judgments that one kind of life or one idea or one time in history is superior to any other. I have wanted to look at what is in front of me and simply try to understand what it says, what was the worldview or life experience that produced these ideas and stories and practices? How could the mind that gave us the creation story, a world of harmony in which no creature, including humans, killed another for food, in which there was no violence, also bring us the idea that we could kill and sacrifice an innocent animal for sins that we committed? What made us think that our lives were so much more valuable than theirs that they should pay for something we did? What made us think we were superior to other creatures and so could eat them?

It is our human tendency to judge ourselves superior that is at the root of any problem I can think of in the world today. And that tendency was hinted at in the creation stories themselves, that beautiful vision of a world in harmony where animals were vegan and had moral responsibility and snakes talked and reasoned and planned. Right there in those creation stories, we have statements about human dominance over animals. Although there are other ways to understand these statements than as statements of superiority, for the most part, we have chosen to understand them exactly that way, and that has created a cultural blind spot.

One of the things I love about the Torah is that it presents revolutionary ideas, that it often even seems to contradict itself — but it offers these amazing perspectives in such a nuanced, subtle way that we are drawn up short, and we start to pay attention: men dominate women, or so some interpreters would say… but wait, in the original Hebrew it actually suggests something different. G-d has no body… but if you read carefully, it’s not so clear. The Land of Israel was given unequivocally and forever to Israel… but read that again, and you’ll discover that too isn’t so clear. We are supposed to dominate and can kill other creatures for food, no problem. Again, look more deeply, and the picture isn’t so sharply drawn. I am continually invited by these ancient texts to dig more deeply, and the more deeply I dig, the more I find that it’s not quite as black and white as it seemed.

Part II: The Ethical Path…Not Always Easy to Find

And so it is with this week’s portion which includes the Rape of Dinah, Jacob and Leah’s only daughter. It is a story that at first glance seems to present a series of actions that are clearly, undoubtedly morally repugnant. But then the details of the story draw us in to look more closely, to consider questions under the surface of the text.

Now I’m going to do something I don’t usually do because I had the opportunity to see this point demonstrated so beautifully on Shabbat. I’d like to share with you the highlights of our discussion, led by Rabbi Tom Samuels. The text is Gen. 34. The rabbi provided several texts to help us parse the text, and you will find them here.

As we discovered, not one character in the story comes out with clean hands “ethically.” Each character is both good and bad, and there are many unanswered questions which, if answered, would change the nature of the story.

- Leah, Dinah’s mother: where was she when her daughter “went out to visit the daughters of the land?” It would have been something major for a young woman from a nomadic temporary settlement to leave her group and enter an alien town alone. But perhaps she didn’t know or was assisting her daughter in pursuing her dreams.

- And how about Dinah? What did she have in mind? Did she consider the consequences of her action for so many others in light of what she knew about her group’s codes and the possibilities of what might happen to her in an alien setting where in all likelihood those same codes were not in operation? Or should we admire her for her agency and boldness? Was she raped and terrified, or did she love Shechem?

- Jacob, the family patriarch, says and does virtually nothing except complain that his sons’ actions endangered his standing in the area and caused the group to have to flee to another location. Jacob doesn’t take steps to rescue his daughter, nor does he call into question the morality of his sons’ actions. Yet his job as patriarch is to keep his group safe and to provide sustenance, and he does this in abundance.

- Most of us would immediately judge the action of Jacob’s sons highly immoral — using the ruse of requiring circumcision as an opening to massacre all the men of Shechem and take their wives and children and livestock and household belongings as booty. But only they took action to retrieve their sister and require justice from the perpetrators of an alleged crime and the community that sheltered the alleged criminal.

- Like Jacob’s sons, Shechem was highly immoral in committing assault…but it’s not so certain that assault was what happened. The translation reads that he “took her and lay with her by force.” The Hebrew, however, reads “וַיִּקַּח אֹתָהּ וַיִּשְׁכַּב אֹתָהּ, וַיְעַנֶּהָ”. The word translated “by force” or in other translations “humbled her” is וַיְעַנֶּהָ (va-y’aneha) and means either defiled her or lay down with her. The second is far more neutral than the first, and neither necessarily means he forced her. And “took her” is the phrase commonly used for any sexual union between a man and a woman including marriage. Certainly many of those unions involved love. According to the story, Schechem loved Dinah: “Being strongly drawn to Dinah daughter of Jacob, and in love with the maiden, he spoke to the maiden tenderly.”

- Hamor seeks a peaceful relationship, but he evidences little concern for his son’s action and its questionable morality nor for Dinah’s situation or the profound offense caused to his neighbors. He never attempts to restore the young woman to her family nor to brings his son to justice. His wish is only to fulfill his son’s request. In joining his son and reporting to his people the agreement he thought he had reached with Jacob and his sons, this phrase creeps in: “Their cattle and substance and all their beasts will be ours, if we only agree to their terms…” Yet this was not part of the agreement the men made. What does this mean?

As we discussed, the text reflects the kind of moral complexity we often face in life, situations where there is no perfect or good or right answer, where no person is perfect, where each acts in ways that are good and bad and ambiguous, where the lines of responsibility are like shifting sands. Yet decisions are made. No decision is a decision. Life and death continue, and history moves forward.

Part III: The Animals’ Story

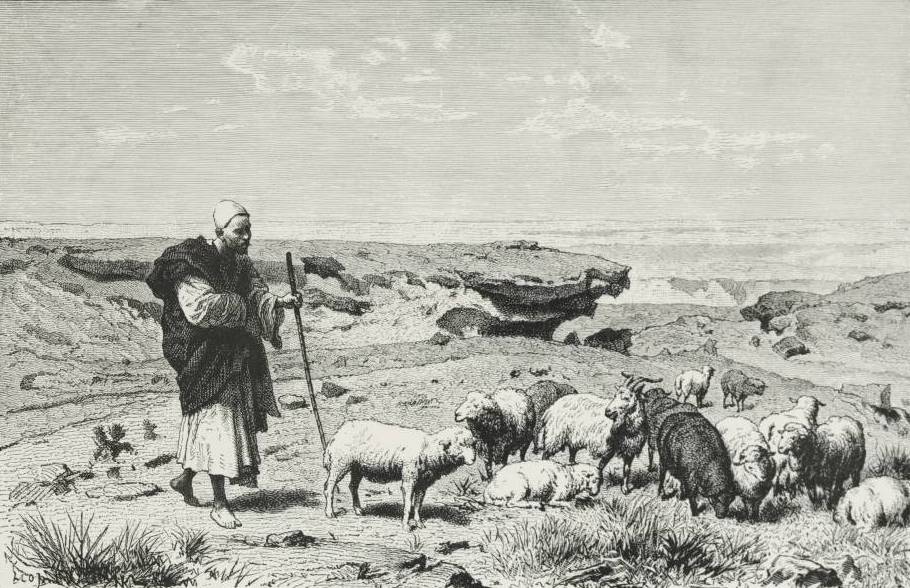

Now I want to take just a moment to explore the ongoing story of the animals, the subtext, in my opinion, of the biblical story. What happens with them in this section of the text?

There are eight references to animals in this portion:

Gen. 32:6 – As Jacob returns to Canaan, he instructs his messengers to go before him and say to Esau: “I have acquired cattle, asses, sheep, and male and female slaves; and I send this message to my lord in the hope of gaining your favor.”

Gen. 32:8 – As Jacob contemplates facing his brother, we learn, “Jacob was greatly frightened; in his anxiety, he divided the people with him, and the flocks and herds and camels, into two camps, thinking, ‘If Esau comes to the one camp and attacks it, the other camp may yet escape.’”

Gen. 32:14-22 – Jacob sends before him gifts for his brother, Esau, including “200 she-goats and 20 he-goats; 200 ewes and 20 rams; 30 mulch camels with their colts; 40 cows and 10 bulls; 20 she-asses and 20 he-asses. These he put in the charge of his servants, drove by drove, and he told his servants, “Go on ahead, and keep a distance between droves.” The servants are to present the gifts in droves, saying with each drove, Your servant Jacob himself is right behind us.”

Gen. 33:13 – After the brothers meet, Esau wishes to accompany Jacob to Seir with his family and flocks. Jacob ambiguously dissuades him saying: “My lord knows that the children are frail and that the flocks and herds, which are nursing, are a care to me; if they are driven hard a single day, all the flocks will die. Let my lord go on ahead of his servant, while I travel slowly, at the pace of the cattle before me and at the pace of the children, until I come to my lord in Seir.”

Gen. 33:17 – Instead of going to Seir, though, Jacob camps at Sukkot and “built a house for himself and made stalls for his cattle.”

Gen. 34:27 – After Simeon and Levi (Dinah’s full brothers) kill the men of Shechem, the other brothers “seized their flocks and herds and asses, all that was inside the town and outside; all their wealth, all their children, and their wives, all that was in the houses, they took as captives and booty.”

Gen. 36:6 – “Esau took his wives, his sons and daughters, and all the members of his household, his cattle and all his livestock, and all the property that he had acquired in the land of Canaan, and went to another land because of his brother Jacob. For their possessions were too many for them to dwell together, and the land where they sojourned could not support them because of their livestock.”

Gen. 36:24 – Esau’s Horite relation, Anah, “discovered the hot springs in the wilderness while pasturing the asses of his father Zibeon.”

So where does our story of the animals take us in this Torah portion? The steady presence of flocks in these narratives signals a semi-nomadic existence. Many flocks, like wives, children and servants are a sign of prosperity. Perhaps most characteristic in this portion, however, is the way the animals are negotiable “items” to preserve the lives of Jacob and his family — or they are booty in war. In either case, they are valuable commodities and the way Jacob uses them demonstrates his lifelong skill in negotiation, as I suggested in another post, his adaptive behavior.

We see a hint of Jacob’s grandmother, Rebekkah, in Gen. 33:13 when Jacob expresses his concern for the well-being of his animals, but this concern, too, is ambiguous. The concern seems “staged” during Jacob’s negotiation to travel unaccompanied through the land with a promise to join Esau in Seir, which he does not do, and we understand he never intended to do. Ultimately Jacob’s holdings allow him to dominate the land of Canaan, according to the promise, as Esau leaves with his flocks to find more room.

In Vayishlach, the animals serve to illustrate more fully Jacob’s character as a negotiator and bargainer, even a trickster. They are commodities … and they are booty — or stolen wealth. But what is stolen, and what is protection? As with so many other elements of the story, the ambiguities leave us wondering, who is right and who is wrong? Perhaps taking the cattle in Shechem was just payback for Hamor’s “real” plan and intention in his offer, a plan the brothers anticipated, to steal everything that was theirs. Hamor hints at this possibility when he tells his people, “Their cattle and substance and all their beasts will be ours, if we only agree to their terms…”

These are domesticated animals, living creatures who become commodities and props for the drama, magnifying Jacob’s persona.

Wow. Beautifully written and thought-provoking.

Thanks, Kathryn! This little project I took on has developed a life of its own and is taking quite a bit more time than I originally imagined. But it’s ok. It fascinates me and I think someday will be useful in ways I don’t yet know.