Listening for the Sounds in Silence

Seven stories illuminate the character and path of Abraham…but five of the seven carry kernels of silence, words unspoken, sounds not recorded. What meanings can we retrieve, buried in the silence?

Seven stories, five with silent spaces:

THREE VISITORS (18:1-18:15)

The three visitors arrive at Abraham’s and Sarah’s tent, bringing the news that Abraham and Sarah will have a child…after agonizing years when they could not conceive. Almost all the conversation in this segment is between Abraham and the guests, establishing Abraham’s commitment to hospitality. When Abraham persuades the visitors to stay for a meal, he rushes to gather the food for the feast and commands Sarah to make cakes — quickly, a command she obeys without recorded comment. When the visitors make their announcement, Sarah laughs — silently, to herself. When the visitors question her soundless laughter, they inquire of Abraham, not Sarah. Frightened by the visitors’ ability to see into her deepest thoughts, she finally speaks, lying, saying she did not laugh. Does Sarah’s silent laughter hide years of pain and fear and frustration? The future for a childless woman is uncertain and fragile in a time when a woman is supported first by her father, then her husband, and if widowed, her inheriting son — a time when a woman’s purpose, in her community and for herself, is defined by bearing children.

ARGUMENT WITH G-D (18:16-18:33)

In one of two stories without an actor who doesn’t speak, Abraham carries on an extended conversation directly with G-d, establishing Abraham’s sense of justice. He pleads eloquently and forcefully on behalf of the cities of the plain, Sodom and Gomorrah, asking G-d to spare them if fifty innocent are found, forty-five, forty, thirty, twenty, ten. The story is remarkable for Abraham’s volubility as well as the content of his message, questioning and reminding G-d to be just by not punishing the innocent with the guilty. For all of Abraham’s anxious volubility, what we don’t hear is, what in Abraham’s history and experience with G-d would make Abraham feel the need to “argue?” Why does he question the justice of an outcome, whatever it is? Still, this is one of two stories in seven where all those present, Abraham and G-d, speak and hear.

TWO VISITORS, TWO DAUGHTERS (19:1-19:38)

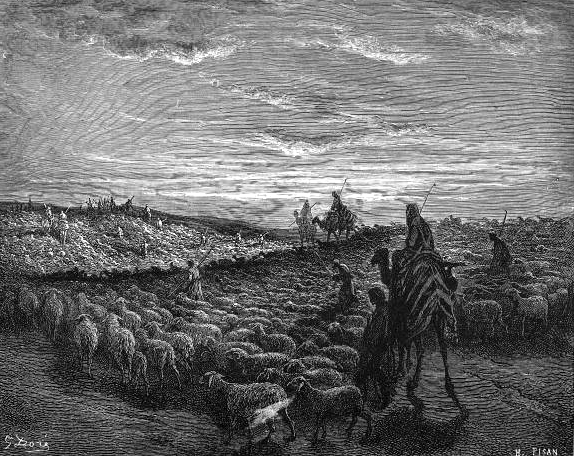

Abraham’s visitors move on, but now they are two. They arrive in Abraham’s nephew, Lot’s, home town, Sodom. Lot’s action when he sees them parallels Abraham’s in some ways when the three visitors arrived at Abraham’s and Sarah’s tent. He urges the visitors to come in and enjoy food as Abraham did…but Lot prepares the food himself, including the bread. Where are the women of the household? We see and hear nothing of them until Lot offers his daughters to the men and boys of Sodom in place of the visitors whom they demand. Lot says, “I have two daughters who have not known man…do to them as is good in your eyes.” This is the first mention of anyone in the household other than Lot, and no words are recorded from the daughters. Whether or not Lot’s action was praiseworthy in the context, imagine the terror the daughters must have felt. Their lives were about to change radically, probably end, if they became substitutes for the visitors as the objects of sexual assault. And finally, after the destruction, Lot’s wife comes into view momentarily as she looks back on the destruction and turns…silently…to a pillar of salt. Her sorrow and terror are also not recorded.

The daughters who were silent as their father offered them up for assault in place of the visitors are now talkative as they discuss and carry out a plan to fulfill their lives’ meaning in their restricted circumstance. Noah sleeps after too much wine, knowing nothing, the silent victim of his daughters’ strategy. Would he have agreed to the plan consciously? How would he have fulfilled the commandment, p’ru u’r’vu (be fruitful and multiply)? What a sad and desperate situation, living in a cave overlooking the devastated landscape, isolated from the society he so desperately wanted to join, without even the wife who bore their children and shared a life with him.

ABRAHAM & ABIMELECH…AGAIN (20:1-20:18)

Once again, Abraham presents his wife, Sarah, as his sister to prevent attacks because those more powerful than he might want his wife and would take her by force. This time, unlike the earlier occurrence with Pharaoh, Abraham doesn’t speak with Sarah, requesting her cooperation. He just presents her as his sister, and King Abimelech of Gerar “had Sarah brought to him,” that is, brought to his harem. G-d comes to Abimelech in a dream, warning him of Sarah’s real status and the punishment that will come to him and his kingdom. Abimelech reproaches G-d in similar terms to those Abraham uses in his Argument with G-d: “Will You slay people even though innocent?” He pleads ignorance, and G-d commands him to return Sarah to her husband.

Abimelech speaks to his servants, telling them what happened, then summons Abraham, demanding to know why Abraham brought this guilt on Abimelech and his kingdom. Abraham explains himself, saying, “I thought…surely there is no fear of G-d in this place, and they will kill me because of my wife…And besides, she is in truth my sister, my father’s daughter though not my mother’s.” Abimelech gifts Abraham with sheep and oxen and restores his wife, inviting him to settle where he wishes in Abimelech’s land. And to Sarah, he says, “I herewith give your brother a thousand pieces of silver; this will serve you as vindication before all who are with you, and you are cleared before everyone.” Is there a hint of sarcasm when Abimelech refers to Sarah’s husband as her brother? In any case, events swirl around Sarah, she is transferred household to household, and throughout, her words and thoughts are never reported. She is silent as her husband misrepresents her and another man takes her into his household.

BIRTH OF ISAAC (21:1-21:21)

Sarah conceives and bears a son, as G-d promised her through the three visitors to the tent. Abraham names his son Isaac, connecting him to Sarah’s silent laughter, and at eight days old, Abraham circumcises him. Then Sarah finally finds her voice, expressing her joy after all these years of disappointment and pain: “G-d has brought me laughter; everyone who hears will laugh with me.” Further, she demands that Abraham cast out “that slave-woman and her son,” Hagar, to whom Sarah sent her husband when Sarah was unable to conceive, and Ishmael, Hagar’s son. Suddenly Sarah, a woman who remains silent through two occasions when her husband passes her off as his sister, allowing her to be taken into the harems of others, and who laughs to herself when told she would conceive in her old age, then lies about her silent laughter out of fear…has a lot to say. She is concerned for her son, Isaac’s, inheritance. The story reports Abraham’s feelings of distress, and G-d speaks to Abraham telling him not to be distressed, to follow whatever Sarah tells him to do, a reversal of their roles.

The next day, Abraham gives Hagar bread and a skin of water to carry along with her child, Ishmael, and he sends her away. Hagar wanders, with her son, in the wilderness of Beersheba until the water runs out. Despairing and unable to bear watching her son die, she leaves the child under a bush and sits down at a distance, bursting into tears. In the next line, the story tells us, “G-d heard the cry of the boy, and an angel of G-d calls to Hagar from Heaven and says to her…” Hagar, silent throughout her ordeal, finally weeps with fear and despair, and G-d hears…not Hagar, but her son, although the story reports no sounds from him. G-d speaks to Hagar, giving her G-d’s promise for Ishmael’s future and showing them a well of water.

In The JPS Torah Commentary for Genesis, editor Nahum Sarna notes how Yishmael recedes into the silence of history with verbal cues. In the course of this story, which unfolds from Gen. 21:1-21, Yitzhak’s name appears 6 times. The root of his name, ts-h-k (associated with laughter), occurs “suggestively” 3 times. Conversely, Yishmael’s name appears not at all, although the word “boy” with reference to Yishmael appears 6 times. The root of the name Yishmael, sh-m-‘ (associated with hearing), occurs “suggestively” 3 times. These skillful verbal cues elaborate the silent theme associated with Yishmael in this story…the boy left under a bush by his despairing mother, a mother who weeps for her son and G-d who hears her silent son.

ABRAHAM & ABIMELECH REDUX (21:22-21:34)

In a brief transitional story, the second of two without a silent actor, Abimelech once again meets with Abraham, this time bringing along Phicol, chief of his troops. On this occasion, equals meet, with King Abimelech seeking a pledge of loyalty from Abraham, the sojourner in his land. Abraham makes that pledge, then reproaches Abimelech for the well Abimelech’s servants seized. Again, Abimelech pleads his innocence on the basis of lack of knowledge. Abimelech and Abraham now make a “pact,” sealed by a gift from Abraham to Abimelech of sheep and oxen. Abraham then pays Abimelech with seven ewes as proof that he, Abraham, dug the well. Their business together concluded, Abimelech returns to the land of the Philistines, and Abraham plants a tamarisk at Beersheba, invoking the name of the Lord.

AKEDAT YITZHAK – THE BINDING OF ISAAC (22:1-22:24)

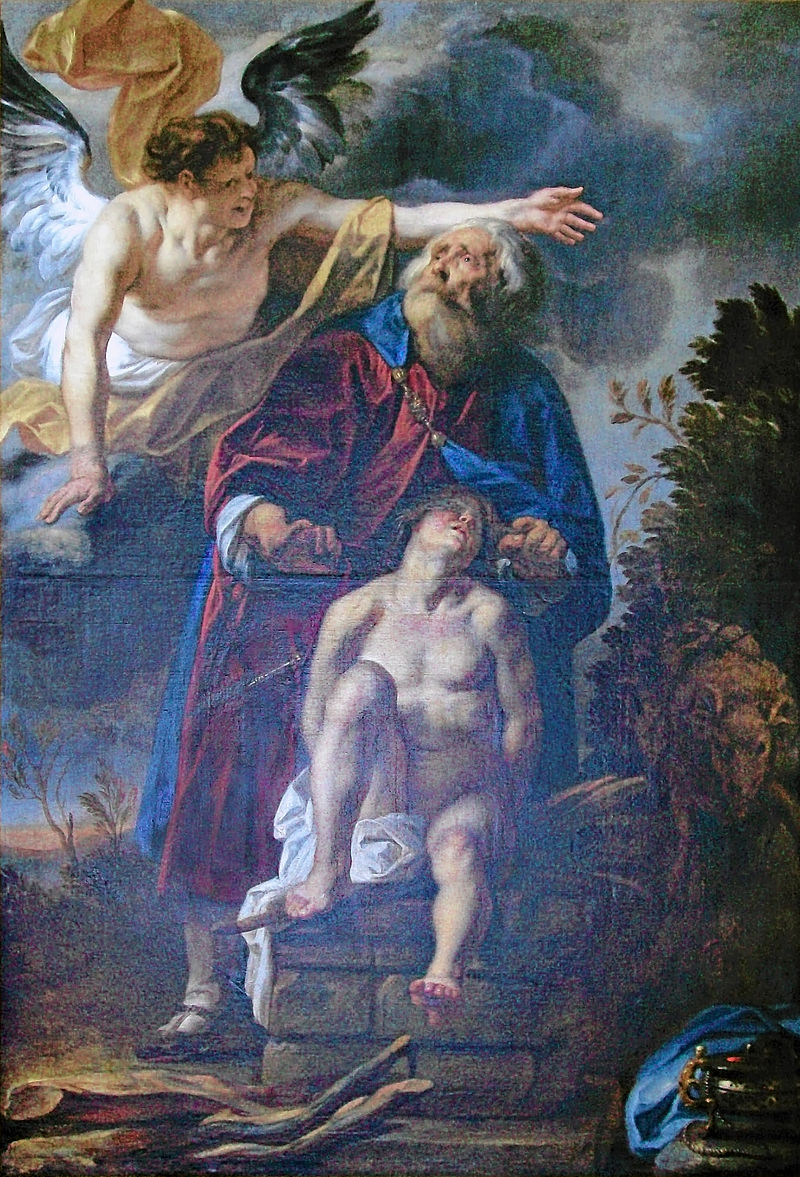

The Binding of Isaac, Abraham’s final test of faith, climaxes this seemingly unrelated series of seven stories which are, nonetheless, intimately linked through verbal cues and parallelisms. The story is filled with silences, beginning with the somber silence that pervades the scene of Abraham preparing to go on a journey to sacrifice his son. Despite the eloquence of his pleas on behalf of Sodom and Gomorrah, Abraham is silent in response to G-d’s command that he “Take your son, your favored one, Isaac, whom you love, and go to the land of Moriah, and offer him there as a burnt offering on one of the heights that I will point out to you.”

Just let that sink in for a moment. Four identifications to make certain there is no doubt. G-d is demanding that Abraham sacrifice his future, a promise finally fulfilled late in his life. Abraham already unwillingly gave up his first son, Ishmael, on G-d’s instruction. Now he is being asked to give up his son, Isaac, the one he favors, a repository of his love and hope for the future — and he must do that in a most horrifying way — he must tie him down, put a knife through him and burn him on the altar. Abraham’s response is fiercely and dutifully silent.

Imagine the buried pain in the conversation between Abraham and his beloved son, Isaac, as they walk toward what Abraham believes will be his awesome duty, the sacrifice of his son. “Father!”…”Yes, my son…” “Here are the firestone and the wood; but where is the sheep for the burnt offering?”…”G-d will see to the sheep for His burnt offering, my son.” And the two of them walked on together.

What did Isaac think as his father, Abraham, bound him and laid him on the altar on top of the wood? As Abraham picked up the knife with the intent of killing him? We don’t know. The moment is buried in silence. And then, in this awful moment, a moment suspended in silence, G-d, who spoke with Abraham directly, who conversed with him, with whom Abraham argued about Sodom and Gomorrah, sends a messenger to hold Abraham back from the terrible deed. Abraham looks up, and his eye falls on a ram, caught in a thicket by its horns. Without hesitation, Abraham goes and takes the ram and offers it as a burnt offering in place of his son.

But the silence continues. Imagine the terror of the ram, first trapped, then bound on an altar for slaughter. It’s hard to imagine the ram’s terror wasn’t finding expression in bleating, that there wasn’t a struggle. The story doesn’t report that — the scene remains submerged in a deep, impenetrable silence.

G-d speaks with Abraham one more time…and again, after so many direct meetings, real conversations, this last one, following the horrifying silent moment on Mt. Moriah, is through a messenger.

Everything changed in that terrifying moment, as much as it changed when Adam and Eve ate from the Tree or Noah entered the Ark with his family and fellow creatures. We are a long way from the vision of the Garden.