I’m teaching a short four session class on Bible. So far my focus has been on the first chapters of Genesis and the middle section of Leviticus, especially chapter 16, the Yom Kippur ritual. In our last week, we will examine the 10 Things or Words, better known as the 10 Commandments. I also hope to touch on the extraordinarily beautiful chapter 25 in Leviticus, about a Shabbaton for the land and the Jubilee Year.

Any text has something to communicate. Some texts do a better job of that than others. I think the first five books of the Bible do a consummate job, but it’s difficult for us to receive the communication, as relevant as it may be for us today, because of its mode of presentation in myth, ritual practices and legal codes and because of our American cultural isolation from the life experience that inspires this text. If we decode those forms, though, and if we can find ways to identify with the experience of destruction of a nation and exile, we find pervasive and powerful messages for our times.

For many of us, certainly the secularists among us, the first five books of the Bible, the Torah, are difficult to understand in meaningful ways. Myth is just…well, myth. The rituals of Leviticus, purifications from childbirth, death, menstruation, seminal emissions and leprosy, are alienating. Even the legal codes, with the exception of soaring passages here and there, can be somewhat opaque. What significance can all the details related to a goring ox have for contemporary urban dwellers so far from that world?

Beyond that, many of us live in an insular situation. Poverty, systemic discrimination, bloodshed (even for our own food), brutality, the instability and terror of living in a war zone…these are all things that if they are in our consciousness at all are likely at its periphery. It requires significant effort to identify with others’ experience so different from our own. It is difficult to understand the profound ideas of the biblical text and its pervasive concern with and response to bloodshed and injustice when we are so insulated from even the normal processes of life and death in our daily lives.

THE LANGUAGES OF THE TEXT

So how do we begin to examine this text and try to understand it? One way is to explore how these three forms, myth, ritual practice and moral legislation, speak. The tools of literary analysis, using the evidence of the text itself, offer a path into the material.

Using this approach, we discover that the first chapters of Genesis and the book of Leviticus make the same set of statements in different ways: Genesis relates a theology and an ontology and outlines a paradox at the root of human existence through story. The rituals of the Purity Code and the ethical legislation in the Holiness Code convey the same themes.

In the narrowest terms, the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil points to the Holiness Code, with its emphasis on ethical relations between the Israelites, their neighbors and their world, and the Tree of Life points to the Purity Code, with its emphasis on birth and death, sexuality and procreation, and leprosy or organic decay.

The first theme is about how creation reflects and is like its creator in that it is pervaded by ethical consciousness. The second half of Leviticus focuses on the specifics of how the Israelites are to express that in their local community. The second theme is about how creation is different from its creator. Accordingly the first half of Leviticus focuses on how G-d can live among the Israelites post-Garden given that profound difference.

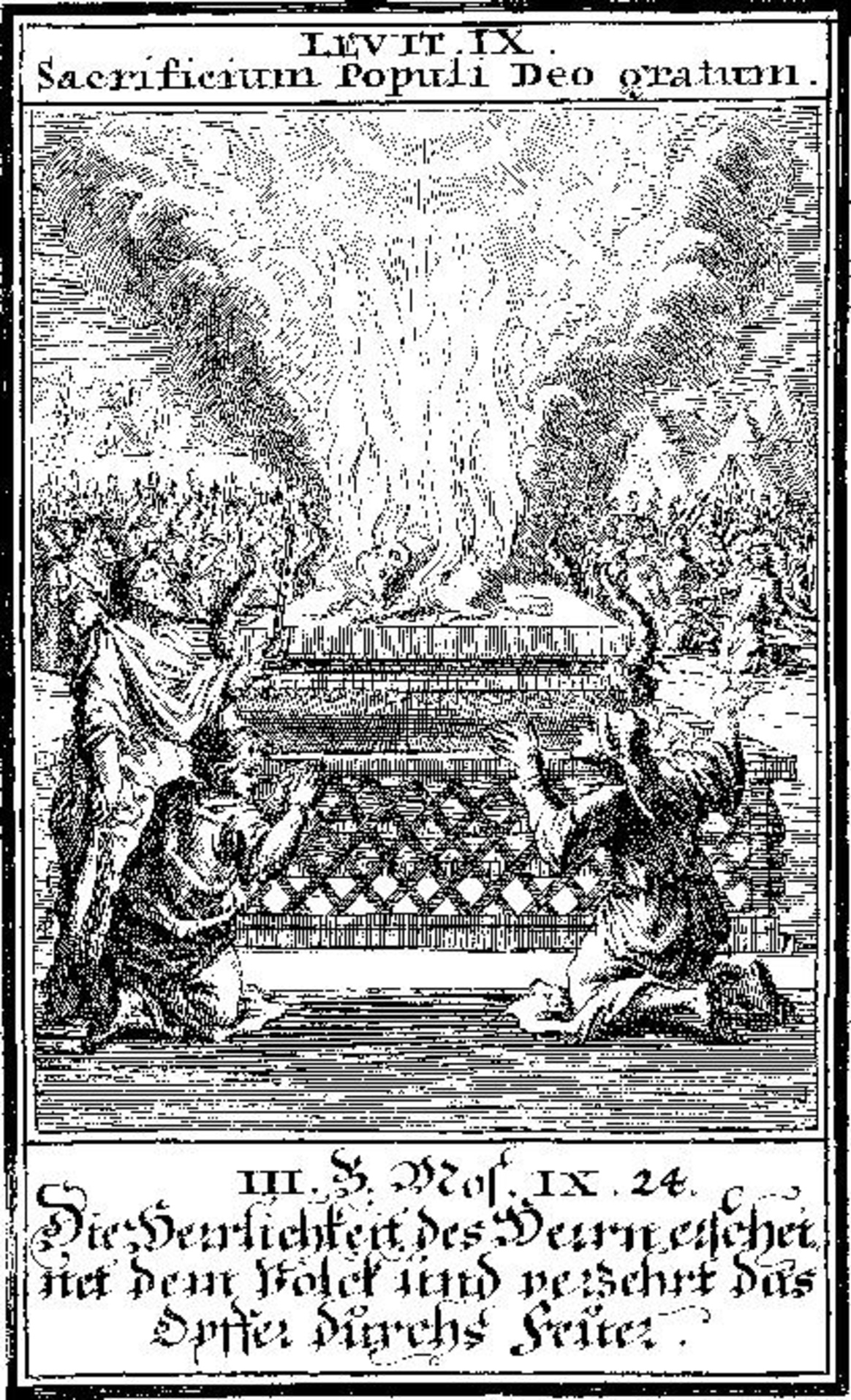

The two goats in the Day of Atonement ritual, the goat for the Lord and the goat for Azazel, remove both ethical sins, sins against one’s neighbor, and impurities that stand between the Israelites and their G-d. The dual action reestablishes a coextensive relationship between G-d, creation and human beings in this local community. It recreates the Garden in this temporal space.

When we use the text itself, its intra-textual allusions, its internal structures, its Hebrew vocabulary, its repetitions — and its repetitions with changes, we can see that. We also might discover it says some things that surprise some of us, upending our assumptions.

SOME THINGS THE FIRST 5 BOOKS OF THE BIBLE SAY

Here are samples of statements the text makes that we discover using literary tools:

- In the Israelite cosmos, creation is ordered and coextensive with transcendence, and an ethical consciousness pervades it all.

- Male and female are created simultaneously, together in the image of G-d.

- G-d and human beings are like each other in some ways and in other ways profoundly different. They share with G-d and the rest of creation ethical consciousness and responsibility. The relationship between the Israelites and their neighbors, even the rest of creation, is governed by ethics.

- Human beings, like the rest of creation, are different from G-d in that they are bound by the laws of nature: birth, death, sexuality and procreation, and disease or organic decay. In addition, creation is differentiated. G-d is a unified consciousness. This should be a cause of some humility. Certainly it is a cause for reflection on how G-d can be in creation, living among a group of people, engaged in an intimate relationship. The relationship between G-d and G-d’s people is governed by ritual.

- There is more than one way to think about the meaning of the event in the Garden, the “meal in the Garden” when we look at multiple meanings and associations to the word, arum (usually translated naked). What if we read that, “prudent,” as it is in Job? Human beings eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil bringing consequences for all of creation. Their eyes are opened, and they realize the enormity of their impulsive action. The Torah, then, urges “prudent” action, conscious choices in full consideration of consequences and implication.

- Ethical intelligence pervades everything, transcendence, all of creation, the animal world, and human life. Whether conscious, instinctive or impulsive, action in one realm impacts all realms.

- A recurring motif of creation and rollbacks of creation tells us that widespread or communal failures to exercise ethical consciousness return us to a dark, empty, barren pre-creation state. We see this motif in the Flood story of Genesis 6-8, and we see it in the 10 Plagues of Exodus 7-13 as well as in other sections of the Torah and in the books of the Prophets. This idea has enormous meaning for us today in relation to problems we face in human, environmental, animal and food justice.

- Bloodshed and violence are fundamental and endemic problems in our world. In the biblical world, this translates to a guide to establishing justice and compassion within a local community.

- The structure of government in local communities is not at issue: what is at issue is the extent to which a society extends holiness by establishing justice and exercising effective compassion.

THE PROJECT OF THE HEBREW BIBLE

The first chapters of Genesis (myth) present a vision of an ideal world, a world in harmony and without bloodshed and violence. These chapters make a set of important statements about the nature of transcendence and creation and our role in creation.

Then we get another picture, a picture of the world as it was then and remains today — but we get more than a realistic graphic. We get a guide for living in that world, extending the boundaries of holiness, mediated through the local communal experience and practices of one group, a group tasked with recreating the Garden in its midst. The Purity and Holiness Codes of Leviticus make the same statements as the myths of Genesis, describing how to create that Garden in the real world through the ritual practices and ethical legislation that teaches and shapes a community.

The 10 Commandments set up an overarching framework for relationships, G-d, all of humanity and creation, then focus in on a local community of “neighbors.” The communal mission is to create a Garden in their midst, where people live in correct relationship to their world and their neighbors and G-d dwells among the people. Following the teachings within this framework leads to “life.” Abandoning these teachings leads to pre-creation darkness, emptiness and barrenness.

OUR EXPERIENTIAL DISTANCE FROM THE TEXT

My own understanding of the text was greatly assisted by a teacher who reminded me that we always have to ask what questions a text comes to answer? And that is the rare moment when I turn to source criticism for help in my understanding.

Many scholars think the final redaction of the Torah came in the mid 5th century b.c.e. At that time, Ezra, the priest, and Nehemiah, the governor, returned to the land of Israel from Babylonian exile to meld returnees and some who never left into a cohesive community. Life in Israel was devastated 140 years before in 586 b.c.e. when the nation and its center, the Temple in Jerusalem, was destroyed. After much bloodshed and many deaths, the people were sent into exile. When a small part of their descendants returned, they came to an impoverished land and faced an almost insurmountable task of rebuilding a nation in the midst of hardship and intra-communal bickering. While those who remained and those who returned had not personally witnessed the devastation, it was surely emblazoned on their consciousness, its effects enduring.

We would, perhaps, better understand those difficult times today if we lived in Syria or any of the other deeply troubled, war-torn, suffering or poverty-stricken corners of the world. We would understand how impulsive actions, envy, greed, the arrogance of power and the failure to extend justice in the world result in the destruction of civilizations and impoverishment of the planet. We would understand the experience of a rollback of creation and our responsibility in it. And we would understand the universality of human experience and how this text speaks directly to it.

In my imagination, the returning community would have confronted these questions: Why did this happen to us, and how can we avoid it happening again? Where is G-d, and how can G-d walk again in our midst? And how can we forge ourselves into a unified community to move forward in this new environment? The answers to the first two questions shape the answer to the third.

And it is at this point that I end the class, hoping that I have opened some possibilities for peering into difficult material and considering what it might be trying to say, what meaning it might have in our time:

- What is the human relationship with transcendence, and what implications does that have for our lives in this world?

- What does it mean that all of creation is coextensive with transcendence although profoundly different from G-d?

- That ethical consciousness pervades everything that is?

- That human beings, male and female together, are “in the image” of G-d?

- That impulsivity and imprudence have consequences?

- What are the fundamental challenges in creation, and how do we respond to them?

- What is the relationship between G-d and human beings, between human beings and the rest of their world?

- What is the spiritual and ethical significance of being embodied?

- How can we live in community? What is the relationship between the community and the individual?

- Should politics be local?

- What is our task as human beings on this planet?

The demand I hear most clearly coming from this text is the one for conscious choice. Impulsivity brought catastrophe to creation. When Adam and Eve’s eyes opened and they were “prudent,” they realized the grave consequences of their impulsive action. The consequences remain with us according to this story, but that defines purpose, extending holiness, or justice and compassion, the products of ethical consciousness, throughout creation.

For more, visit my blog, vegetatingwithleslie.org, “Like” me on FaceBook/Vegetating with Leslie or follow me on Twitter, @vegwithleslie.